Concerning a Variant in the de Fuentes Manuscript

In his De Orbe Novo (1516), Peter Martyr of Angleria records a cosmogony of the Taíno people of Hispaniola, derived from the earlier report of the friar Ramón Pané. Pané notes that his informant, a baptized cacique named Íñigo, told the story reluctantly and in fragments, and that he himself had to assemble it into coherent form.

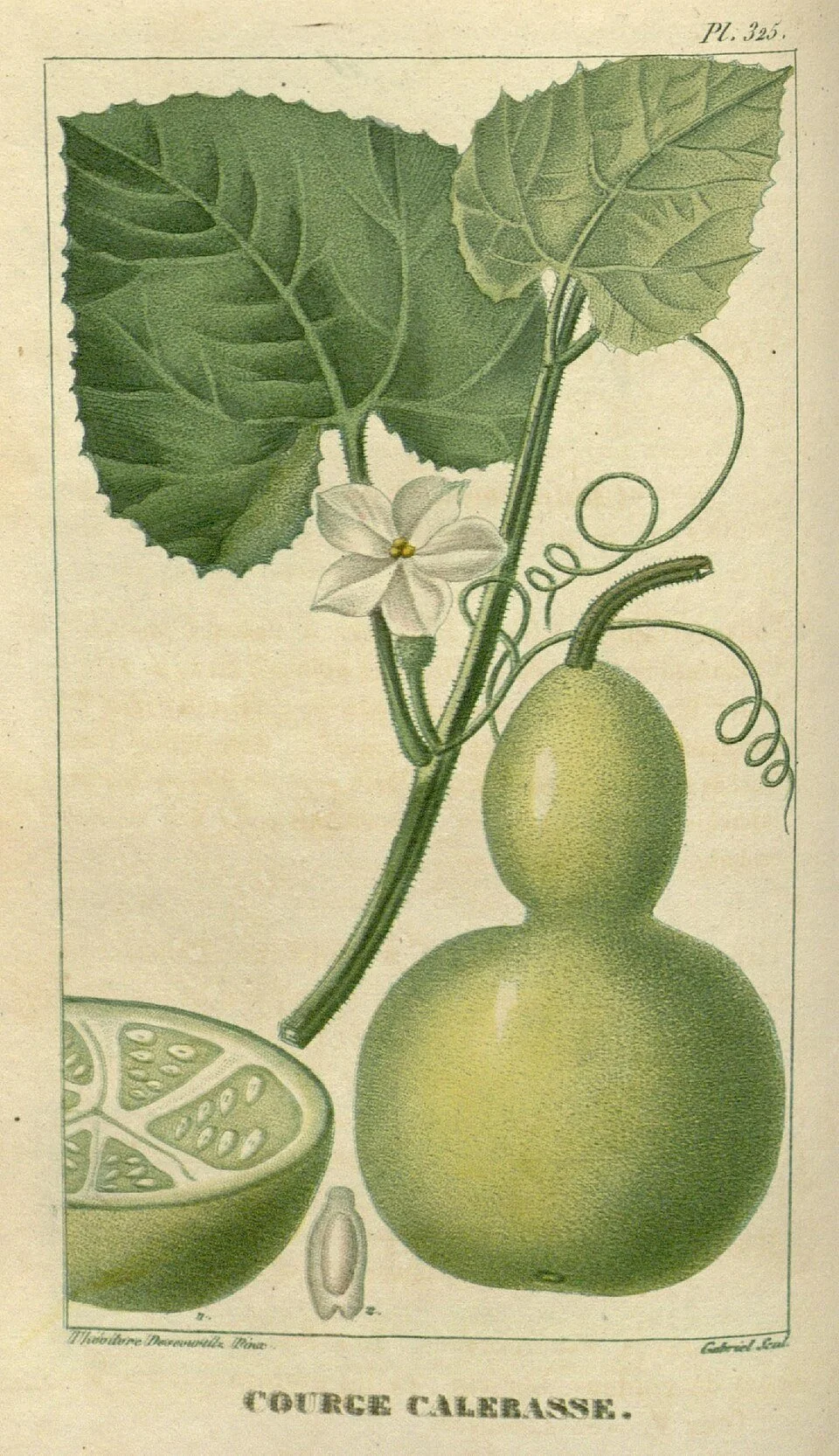

The Taíno say that in the time before time there was a great chief whose name is lost, whom they called only Yaya, which Íñigo rendered into Castilian as el más grande, “the greatest.” Yaya had a son, and because he feared the son would one day overthrow him, he killed him. Following Taíno custom, he placed the body in a gourd and hung it from the rafters of his dwelling.

Seized by grief (or by something for which Pané found no Castilian word) Yaya asked his wife to bring him the gourd. When he looked inside, he saw that his son’s bones had become fish, his hair sea-grass, and his blood a vast and endless sea. From that day the village never went hungry. When asked how a finite vessel could contain an infinite ocean, Íñigo replied that the gourd was also infinite, though it did not appear so.

One day Yaya left to visit the plain of his ancestors, and in his absence four brothers came upon his house. These brothers had been born simultaneously, and their mother had died in childbirth. Pané names only one, Deminán Caracaracol; Íñigo would not name the others, saying only that there were four because “that is how many directions there are in such stories.” They found the gourd, looked upon the sea within it, and resolved to take it for themselves. But Yaya returned at that moment, and the brothers, startled, dropped the gourd. It broke against the ground, and the sea rushed out and filled the valleys and covered the plains, leaving only the mountain peaks standing above the waters.

The Taíno word for “gourd” shares a root with their words for “skull” and “womb.”

The Franciscan Álvaro de Fuentes, writing in 1623, records a variant collected in the eastern mountains: the gourd did not break; the sea dried up inside it, and the islands are what remained. De Fuentes credits the story to an unnamed Taíno elder, but in the margin of the manuscript, a later hand has struck through this attribution and written simply: de Fuentes himself.