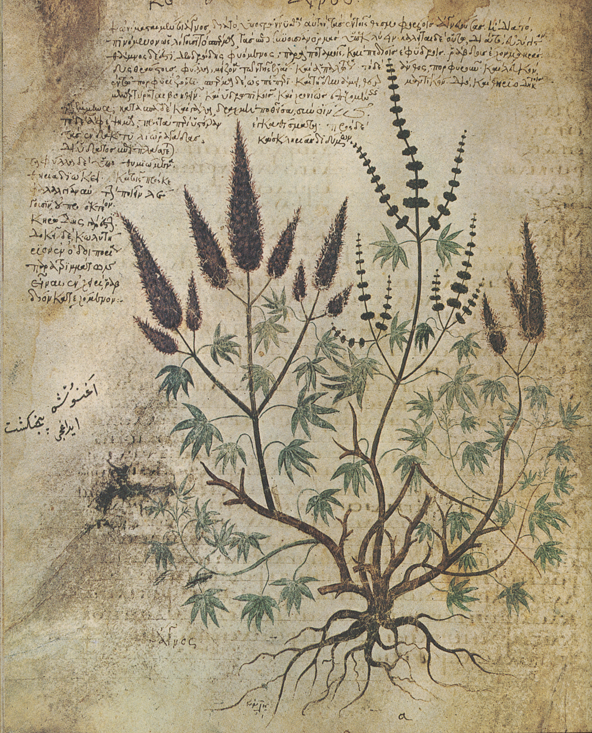

The following is a translation of Galen’s Simple Drugs Book 6, chapter 1, on abrotonum (probably Artemisia abrotanum L.). While not a preface strictly speaking, this chapter (and book 6 chapter 2, up next week) still include useful summaries of what Galen has said he is up to in books 1–5 and also offer examples of his method in practice. It has been translated in part in an important paper, Philip van der Eijk 1997 “Galen’s use of the concept of ‘qualified experience’ in his dietetic and pharmacological works.”

Galen’s Simple Drugs 6, Chapter 1

Concerning abrotonum, it is not necessary to add anything about the form (idea) or particular activities (energeiai) of this herb to what has already been written by so many different men, since they have indicated them, if not distinctly, at least clearly [1]. I will also say more about it in my treatises on Compound Drugs and on Common Medicines (Euporistai), and now and then in the books on The Therapeutic Method when needed. However, I have proposed from the beginning to examine only the universal capacities (dunameis) of all drugs, which I will do in what follows, and, starting with abrotonum, state that it is hot and dry in capacity, placed somewhere in the third order and degree after the moderate ones, possessing a certain diaphoretic and cutting capacity. When taken, its powder has the same capacity as what is flesh-producing and stinging [2].

I have mentioned many times before that this rank is estimated relative to the well-mixed nature. I have discovered its mixture not least by inferring it from its taste, for it is considerably bitter. This kind of flavour, being earthy in substance, was shown to be thinned by abundant heat, so that it heats and dries in no inferior manner. Moreover, after testing it precisely using qualified experience, about which I have spoken many times, I found this drug to be composed from this same mixture [3]. For if you grind the foliage together with the flowers (for the rest of the stalk is useless) and apply it to a clean wound, it is obviously stinging and irritating, and if you soak it in oil and then want to apply it to the head or the belly, it will be found to heat intensely. And also, in the case of those who are seized periodically by shivering, if you rub them with it before the attack, they will shiver less, but the heating is sensed immediately when it is applied. And it is likely that it kills worms because it is bitter and this is clear even before the experience, if we recall my comments in the fourth book where I discussed the nature of the bitter flavour. You will immediately observe that it has a certain diaphoretic and cutting capacity. However, you will also be able to infer primarily from its taste that necessarily it has this quality more than absinth. For abrotonum shares very little in sourness, while absinth shares not a little. Furthermore, abrotonum is bad for the stomach, as seriphon also is, while absinth is good for the stomach. For concerning this point, it has been shown earlier that bitterness per se is completely bad for the stomach, while tartness or sourness or astringency in general is good for the stomach. When these qualities are mixed together with one another, the stronger one prevails.

These things are enough for you to know in this treatise, for I will show you in the books on the Therapeutic Method how someone should best use this kind of a drug. And for this reason, do not additionally seek to hear that when it is used as a poultice with boiled quince, [4] or with bread, it heals inflammations of the eyes, or that when it is boiled smooth with cornmeal it disperses tumours. For neither of these remedies nor any others are appropriate for this treatise. Rather, for those who adopt an Empiricist instruction, they are described in the works on Common Medicines, while those who want to practice the art rationally, they need the Therapeutic Method. For as with other drugs someone might do more harm than good with these kinds of reports.

When Hippocrates writes in the Aphorisms [VI.31, IV.570 L.], “pains of the eyes are resolved by drinking neat wine, bath, vapour baths, phlebotomy, or drugs,” although he did not specify what kinds of pains [are resolved by] drinking neat wine, which by baths, which by vapour baths, which by phlebotomy, which by drugs, I think someone might defer to him for three reasons. For, he composed an aphoristic teaching, in which, because of the succinctness of the form, it was mostly acceptable to write in this way; that he wrote about all cures for pains, even if he did not define which of them is suitable for which pain; and finally, very often in his other writings, he provided us with starting points for the specifications of what has been stated in this way [i.e., aphoristically]. Those, however, who write aphoristically and briefly without having written about those aphorisms in other books or in a long and detailed treatise, or who indicate to people a single drug from among the many available, they do more harm than good. For there are many differences among the kinds of eye diseases, and one of them requires the poultice I mentioned, while for other kinds it is harmful. The person who uses it on everyone indifferently will harm many more people than they will help.

In this way, therefore, we must describe not only abrotonum, but also all the other drugs, discovering their capacities for heating, cooling, moistening, or drying from the methods I have frequently mentioned, and, from experience alone, all those things caused by the specific quality of the whole substance. It has also been shown about the kinds of drugs that are deleterious and that are alexeteria and purgatives of the deleterious ones. For it is not possible to produce a rational discovery of these, while only in some cases is it possible to discover some plausible conjecture, for it surely cannot happen in all cases, as I have shown previously. But concerning the capacities discovered in this way, I will discuss them specifically in what follows, after I have gone through, for each kind of drug, the capacities of heating and cooling, moistening and drying, as well as whatever follows from them.[5]

For now, I will conclude the discussion about abrotonum once I have added this much more. The most marvelous Pamphilus, even though he describes this herb first and maintains that he himself has experienced, if not the ones he discusses later, at least this one, he nevertheless makes significant errors, believing it to be the plant called “santonicum” by the Romans. For abrotonum is different from santonicum, just as Dioscorides most accurately described in his third book On Materials, and as all physicians and dry-goods sellers are aware. For there are two types of abrotonum, the one considered male, the other female, as distinguished by Dioscorides, Pamphilus, and many others. Different from this is absinth, which itself needs to be classified into three types: one is called homonymously with the kind “absinth,” such is especially the Pontic kind; another is called “seriphon;” and another “santonicum.” But if someone calls a different one “absinth,” another one “seriphon,” and another “santonicum,” it would not make any difference to our present discussion. For we have not come to distinguish names; we are rather concerned with the things themselves. Since, then, these substances differ clearly from one another in their forms, tastes, and capacities, let them all be called by a single name if one wishes, but let the capacities be precisely described.

We have already stated that the forms have been adequately addressed by Dioscorides and no few others, so there is no need to write down what has been correctly stated before. However, if there is anything about these properties that they left undefined, I will attempt to add it here in order to come to the end of the discussion. Absinth is less hot than the substances we mentioned, as it possesses an extreme degree of astringency. But even if it is composed of finer parts than those, and for this same reason is less thinning than them, it is surely not less drying. Of the others, santonicum, which takes its name from the country of Santoneia in which it grows, is closest in capacity to seriphon, lacking a little bit in the ability of thinning, heating and drying. And seriphon is less warm than abrotonum, but warmer than absinth, while it is considerably bad for the stomach and gives off a certain saltiness with bitterness and has a slight tartness. So, both abrotonum and santonicum are both considerably bad for the stomach. For among them, only absinth, especially Pontic absinth, is good for the stomach because it shares most in astringency. Burnt abrotonum, on the other hand, is hot and dry in capacity, even more than burnt, dry colocynth and dill root. For these are suitable for weeping ulcers as well as those that are crusted over without inflammation, and for this reason it seems especially suited for those on the foreskin. The ash of abrotonum is stinging for all ulcers. And for this reason, it is also suitable for alopecia when mixed with an oil composed of fine parts, like castor oil, obviously, or radish, Sicyonian, or aged, and especially Sabine oil. It also promotes the growth of slow growing beards when combined with any of the oils just mentioned, and no worse than them when wet with mastic fruit oil. For it is rarefying in addition to being composed of fine parts, biting, and hot. It is also especially necessary to recognize these of its capacities, and with that, none of its particular capacities are yet lacking in this treatise.

ἀβροτόνου ταύτης τῆς πόας οὔτε τὴν ἰδέαν χρὴ γράφειν ἐπὶ τοσούτοις τε καὶ τοιούτοις ἀνδράσιν οὔτε τὰς κατὰ μέρος ἐνεργείας ὡς ἐκεῖνοι, κᾂν εἰ μὴ διωρισμένως, ἀλλὰ σαφῶς γοῦν ἐδήλωσαν. εἰρήσεται δὲ καὶ ἡμῖν ἐπιπλέον ὑπὲρ αὐτῶν ἐν τῇ περὶ συνθέσεως φαρμάκων πραγματείᾳ καὶ τῇ τῶν εὐπορίστων, ἔστι δ' ὅτε κᾀν τοῖς τῆς θεραπευτικῆς μεθόδου γράμμασιν, ὅταν ἡ χρεία καλῇ. μόνον δὲ, ὅπερ ἐξ ἀρχῆς πρόκειται, τὰς καθόλου δυνάμεις ἁπάντων τῶν φαρμάκων ἐπισκέψασθαι, τοῦτο κᾀπὶ τῶν ἄλλων μὲν ἕπεται, καὶ νῦν δὲ ἤδη ποιητέον αὐτὸ καὶ λεκτέον ὡς θερμόν τέ ἐστι καὶ ξηρὸν τὴν δύναμιν τὸ ἀβρότονον, ἐν τρίτῃ που τάξει καὶ ἀποστάσει μετὰ τὰς συμμετρίας τεταγμένον, διαφορητικήν τὲ τινα καὶ τμητικὴν ἔχον δύναμιν. τῆς αὐτῆς δ' ἐστὶ δυνάμεως καὶ ἡ τρίψις αὐτοῦ εἰληφυῖα, ὥσπερ τὸ σαρκωτικόν τε καὶ δακνῶδες. ὅτι δὲ καὶ ὡς πρὸς τὴν εὔκρατον φύσιν ἡ τοιαύτη τάξις ἐξετάζεται πρόσθεν εἴρηται πολλάκις.

ἐξεύρομεν δ' αὐτοῦ τὴν κρᾶσιν οὐχ ἥκιστα μὲν καὶ τῇ γεύσει τεκμηράμενοι, πικρὸν γάρ ἱκανῶς ἐστιν. ὁ δὲ τοιοῦτος χυμὸς ἐδείκνυτο γεώδης μὲν ὢν τὴν οὐσίαν, ὑπὸ θερμότητος δαψιλοῦς λεπτύνεσθαι, ὥστε καὶ θερμαίνειν καὶ ξηραίνειν οὐκ ἀγεννῶς. οὐ μὴν ἀλλὰ καὶ τῇ διωρισμένῃ πείρᾳ, περὶ ἧς ἔμπροσθεν εἴρηται πολλάκις, ἀκριβῶς βασανίσαντες ἐκ τῆς αὐτῆς εὕρομεν τὸ φάρμακον τοῦτο κράσεως. εἴτε γάρ κόψας τὴν κόμην ἅμα τοῖς ἄνθεσιν, ἄχρηστον γάρ αὐτοῦ τὸ λοιπὸν κάρφος, ἐπιπάττοις ἕλκει καθαρῷ, δακνῶδές τε καὶ ἐρεθιστικὸν φαίνεται, εἴτε ἀποβρέξας ἐν ἐλαίῳ καταντλεῖν ἐθελήσαις ἤτοι κεφαλὴν ἢ γαστέρα, θερμαῖνον σφοδρῶς εὑρεθήσεται. καὶ μὲν δὴ καὶ ὅσοι κατὰ περιόδους ἁλίσκονται ῥίγεσιν, εἰ καὶ τούτους ἀνατρίβοις πρὸ τῆς εἰσβολῆς, ἧττον ῥιγῶσιν, ἀλλ' οὐδὲ τὴν αἴσθησιν εὐθὺς ἅμα τῷ προσφέρεσθαι λανθάνει θερμαῖνον. ὅτι δὲ ἕλμινθας ἀναιρεῖν εἰκός ἐστι πικρὸν ὑπάρχον αὐτὸ καὶ πρὸ τῆς πείρας εὔδηλον, εἴ τι μεμνήμεθα τῶν ἐν τῷ τετάρτῳ τῶνδε τῶν ὑπομνημάτων εἰρημένων ὑπὲρ τοῦ πικροῦ χυμοῦ τῆς φύσεως. εἰδήσεις δ' εὐθὺς ὡς καὶ διαφορητικήν τινα καὶ τμητικὴν ἔχει δύναμιν. ἀλλὰ καὶ ὡς μᾶλλον ἀψινθίου τοῦτο ὑπάρχειν ἀναγκαῖον αὐτῷ συλλογίσασθαὶ σοι παρέσται πρῶτον μὲν ἐκ τῆς γεύσεως. ἐλαχίστης γάρ τινος μετέχει στρυφνότητος τὸ ἀβρότονον, ἀψίνθιον δὲ οὐκ ὀλίγης· ἔπειτα δὲ κᾀκ τοῦ κακοστόμαχον εἶναι τὸ ἀβρότονον, ὥσπερ οὖν καὶ τὸ σέριφον, εὐστόμαχον δὲ τὸ ἀψίνθιον. ἐδείχθη γάρ καὶ περὶ τούτων πρόσθεν ὡς τὸ μὲν πικρὸν αὐτὸ καθ' αὑτὸ παντελῶς εἴη κακοστόμαχον, τὸ δὲ αὐστηρὸν ἢ στρυφνὸν ἢ ὅλως στῦφον εὐστόμαχον. ἐπιμιγνυμένων δὲ τῶν ποιοτήτων ἀλλήλαις ἡ σφοδροτέρα ἂν ἐπικρατοίη.

ταῦτ' οὖν ἀρκεῖ σοι γινώσκειν ἐν τῇδε τῇ πραγματείᾳ. δειχθήσεται γάρ ἐν τοῖς τῆς θεραπευτικῆς μεθόδου γράμμασιν ὡς ἄν τις τοιούτῳ φαρμάκῳ κάλλιστα χρῷτο. καὶ διὰ τοῦτο μηκέτι ἐπιζήτει ἀκούειν μήθ' ὅτι σὺν ἑφθῷ μήλῳ κυδονίῳ καταπλασθὲν ἢ ἄρτῳ φλεγμονὰς ὀφθαλμῶν ἰᾶται, μήθ' ὅτι διαφορεῖ φύματα σὺν ὠμηλύσει λεῖον ἑψηθέν. οὐδὲ γάρ τούτων οὐδέτερον οὔτε τῶν ἄλλων οὐδὲν τῆς νῦν πραγματείας ἴδιόν ἐστιν, ἀλλὰ τοῖς μὲν ἐμπειρικὴν διδασκαλίαν ποιουμένοις ἐν τοῖς εὐπορίστοις γράφεται φαρμάκοις, ὅσοι δὲ λογικῶς ἀσκῆσαι τὴν τέχνην βούλονται, τῆς θεραπευτικῆς ἐστι χρεία τούτοις μεθόδου. τὰ τε γάρ ἄλλα καὶ βλαβείη τις ἂν μᾶλλον ἢ ὠφεληθείη πρὸς τῆς τοιαύτης ἱστορίας.

Ἱπποκράτει μὲν οὖν ἐν ἀφορισμοῖς γράφοντι, ὀδύνας ὀφθαλμῶν ἀκρατοποσίη ἢ λουτρὸν ἢ πυρίη ἢ φλεβοτομίη ἢ φαρμακείη λύει· μὴ μέντοι προστιθέντι, ποίας μὲν οὖν ὀδύνας ἀκρατοποσία, ποίας δὲ λουτρὸν, καὶ τίνας μὲν πυρία, τίνας δὲ φλεβοτομία, τίνας δὲ φαρμακεία, συγχωρήσειεν ἄν τις, οἶμαι, διὰ τρεῖς αἰτίας. καὶ γάρ ἀφοριστικὴν ἐποιεῖτο διδασκαλίαν, ἐν ᾗ διὰ τὸ σύντομον οὕτω λέγεσθαι συγκεχώρηκε τὰ πολλὰ, καὶ πάντα τὰ ἰατικὰ τῶν ὀδυνῶν ἔγραψεν, εἰ καὶ μὴ διωρίσατο πρὸς ὁποίαν ὀδύνην ποῖον αὐτῶν ἁρμόττει, ἢ καὶ πολλαχόθι τῶν ἄλλων συγγραμμάτων ἀφορμὰς ἡμῖν ἔδωκε τῶν ἐν τοῖς οὕτω ῥηθεῖσι διορισμῶν. ὅσοι δὲ μήτ' ἐν ἑτέροις βιβλίοις ἔγραψαν ὑπὲρ τῶν τοιούτων ἀφορισμῶν μήτε ἐν διεξοδικῇ τε καὶ μακρᾷ πραγματείᾳ, γράφουσιν ἀφοριστικῶς τε καὶ βραχέως, εἴτε τὸ πρὸς τούτοις ἓν ἐκ πολλῶν δηλοῦσιν, εἰς πλείω δὲ βλάπτουσιν ἡμᾶς ἢ ὠφελοῦσι. πολλῶν γάρ οὐσῶν διαφορῶν ἐν ταῖς ὀφθαλμίαις, καὶ μιᾶς μὲν ἐξ αὐτῶν χρῃζούσης τοῦ προειρημένου καταπλάσματος, τῶν δ' ἄλλων βλαπτομένων, ὁ χρώμενος ἐπὶ πασῶν ἀδιορίστως πολὺ πλείους βλάψει ἢ ὠφελήσει.

κατὰ τοῦτον οὖν τὸν τρόπον οὐ περὶ ἀβροτόνου μόνον, ἀλλὰ καὶ περὶ τῶν ἄλλων ἁπάντων γραπτέον ἡμῖν ἐστι, τὰς μὲν κατὰ τὸ θερμαίνειν καὶ ψύχειν ἢ ὑγραίνειν ἢ ξηραίνειν δυνάμεις ἐξ ὧν πολλάκις εἴρηκα μεθόδων εὑρίσκουσιν, ὅσα δὲ κατὰ τὴν ἰδιότητα τῆς ὅλης οὐσίας ἀποτελοῦνται τῇ πείρᾳ μόνῃ. δέδεικται καὶ περὶ τῶν τοιούτων ὡς δηλητήριοὶ τὲ εἰσι καὶ δηλητηρίων ἀλεξητήριοι καὶ καθαρτικοί. τούτων γάρ οὐχ οἷόν τε λογικὴν ποιήσασθαι τὴν εὕρεσιν, ἀλλ' ἢ μόνον ὑπόνοιὰν τινα πιθανὴν ἔστιν εὑρεῖν ἐπὶ τινων· οὐ γάρ δὴ ἐπὶ πάντων γε, καθάπερ καὶ αὐτὸ τοῦτο δεδήλωται διὰ τῶν ἔμπροσθεν. ἀλλὰ περὶ μὲν τῶν οὕτως εὑρισκομένων δυνάμεων ἰδίᾳ ποιήσομαι τὸν λόγον ἐν τοῖς ἐφεξῆς, ἐπειδὰν πρότερον ὑπὲρ τῶν κατὰ τὸ θερμαίνειν καὶ ψύχειν, ὑγραίνειν τε καὶ ξηραίνειν, καὶ ὅσα ταύταις ἕπονται διέλθω καθ' ἕκαστον εἶδος φαρμάκου.

τοσόνδε μέντοι προσθεὶς ἔτι περὶ ἀβροτόνου καταπαύσω τὸν λόγον, ὡς ὁ θαυμασιώτατος Πάμφιλος, καίτοι ταύτην πρώτην πόαν γράφων καὶ τάχ' ἂν εἰ μηδενὸς τῶν ἐφεξῆς, ἀλλὰ ταύτης γοῦν ἐθελήσας αὐτόπτης γενέσθαι, ὅμως ἔσφαλται μέγιστα, νομίζων ὑπὸ Ῥωμαίων σαντόνικον ὀνομάζεσθαι τὴν βοτάνην. διαφέρει γάρ ἀβρότονον σαντονίκου, καθότι καὶ Διοσκουρίδης ἔγραψεν ἐν τῷ τρίτῳ περὶ ὕλης ἀκριβέστατα, καὶ πάντες ἴσασι τοῦτὸ γε ἰατροὶ καὶ ῥωποπῶλαι. τοῦ μὲν γάρ ἀβροτόνου δύο ἐστὶν εἴδη, τὸ μὲν ἄρρεν, τὸ δὲ θῆλυ νομιζόμενον, ὡς καὶ τοῦτο διώρισται παρὰ τῷ Διοσκουρίδῃ τε καὶ τῷ Παμφίλῳ καὶ ἄλλοις μυρίοις. ἕτερον δὲ ἐστιν αὐτοῦ τὸ ἀψίνθιον, οὗ πάλιν εἴδη χρὴ τίθεσθαι καὶ αὐτὰ τριττὰ, ὧν τὸ μὲν τῷ γένει ὁμωνύμως προσαγορεύονται ἀψίνθιον, ὁποῖον μάλιστὰ ἐστι τὸ Ποντικὸν, τὸ δὲ σέριφον, τὸ δὲ σαντόνικον. εἰ δ' ἄλλο μὲν ἀψίνθιον, ἄλλο δὲ σέριφον, ἄλλο δὲ σαντόνικον λέγοι, οὐδὲν εἰς τὰ παρόντα διαφέρει. οὐδὲ γάρ ὄνομα διαιρήσοντες ἥκομεν, ἀλλ' ὑπὲρ αὐτῶν τῶν πραγμάτων σπουδάζομεν. ἐπεὶ τοίνυν καὶ ταῦτα καὶ ταῖς ἰδέαις καὶ ταῖς γεύσεσι καὶ ταῖς δυνάμεσιν ἕτερα σαφῶς ἀλλήλων ἐστὶν, ὀνομαζέτω μὲν, εἰ βούλοιτὸ τις, ἅπαντα διὰ μιᾶς προσηγορίας, ἐκδιδασκέτω δὲ ἀκριβῶς τὰς δυνάμεις.

ἡμεῖς οὖν τὰς μὲν ἰδέας αὐτάρκως ἔφαμεν εἰρῆσθαι Διοσκουρίδῃ τε καὶ ἄλλοις οὐκ ὀλίγοις, ὥστ' οὐ χρὴ γράφειν αὖθις ὅσα τοῖς πρόσθεν ὀρθῶς εἴρηται. εἴ τι δ' ἐν ταῖς τούτου δυνάμεσιν ἀδιόριστον ἐκεῖνοι παρέλιπον, οὗ δὴ χάριν ἐπὶ τήνδε τὴν ἔξοδον ἀφικόμην, ἐγὼ προσθεῖναι πειράσομαι. τὸ μὲν ἀψίνθιον ἧττόν ἐστιν τῶν εἰρημένων θερμὸν, ὡς ἂν πλείστης μετέχων τῆς στύψεως. εἰ δὲ καὶ τοῦτο λεπτομερὲς ἧττον ἐκείνων, καὶ λεπτυντικὸν δὴ κατὰ τὸν αὐτὸν τρόπον ἧττον ἐκείνων, οὐ μὴν ἧττόν γε ξηραντικόν. τῶν δ' ἄλλων τὸ μὲν σαντόνικον ἀπὸ Σαντονείας χώρας, ἐν ᾗ φύεται, τὴν προσηγορίαν ἔχον ἐγγυτάτω τὴν δύναμίν ἐστι τοῦ σερίφου, βραχεῖ τινι λειπόμενον ἐν τῷ λεπτύνειν τε καὶ θερμαίνειν καὶ ξηραίνειν. αὐτὸ δὲ τὸ σέριφον ἧττον μὲν θερμὸν τοῦ ἀβροτόνου, θερμότερον δὲ ἀψινθίου, κακοστόμαχον δὲ ἱκανῶς καὶ ὡς ἂν ἁλμυρίδα τινὰ σὺν πικρότητι ἀποφαῖνον, ἔτι τε τῆς στρυφνότητος ὀλίγον μετέχον. οὕτω δὲ καὶ ἀβρότονον καὶ σαντόνικον ἱκανῶς ἐστι κακοστόμαχον. μόνον γάρ ἐν αὐτοῖς τὸ ἀψίνθιον καὶ μάλιστα τὸ Ποντικὸν εὐστόμαχόν ἐστιν ὅτι πλείστης μετέχει στύψεως. ἀβρότονον δὲ κεκαυμένον θερμὸν καὶ ξηρόν ἐστι τὴν δύναμιν, ἔτι μᾶλλον κολοκύνθης ξηρᾶς κεκαυμένης καὶ ἀνήθου ῥίζης. ἐκεῖνα γάρ ἕλκεσιν ὑγροῖς τε ἅμα καὶ χωρὶς φλεγμονῆς τετυλωμένοις ἁρμόττει, καὶ διὰ τοῦτο μάλιστα τοῖς ἐπὶ πόσθαις αἰδοίου συμπεφωνηκέναι δοκεῖ. τοῦ δὲ ἀβροτόνου ἡ τέφρα δακνώδης ἅπασιν ἕλκεσιν ὑπάρχει. καὶ διὰ τοῦτο καὶ πρὸς ἀλωπεκίας ἁρμόττει σὺν ἐλαίῳ λεπτομερεῖ, κικίνῳ δηλονότι ἢ ῥαφανίνῳ ἢ Σικυωνίῳ ἢ παλαιῷ, καὶ μάλιστα τῷ Σαβίνῳ. καὶ γένεια δὲ βραδέως ἀνιόντα προκαλεῖται μετὰ τινος τῶν εἰρημένων ἐλαίων ὅτου δὴ, καὶ οὐδὲν δ' ἧττον ἐκείνων σχινίνῳ δευόμενον. ἀραιωτικὸν γάρ ἐστι πρὸς τῷ λεπτομερὲς εἶναι καὶ δακνῶδες καὶ θερμὸν, ἃς δὴ καὶ μάλιστα χρὴ γινώσκειν τὰς δυνάμεις αὐτοῦ καὶ μηδὲν ἔτι τῶν κατὰ μέρος ἐν τῇδε τῇ πραγμανείᾳ δεῖσθαι.

Galen, On the Capacities of Simple Drugs, VI.1, XI.798–807 K.

[1] Including many of the writers he has just mentioned in the preface to book 6. For the construction, see also Alim. Fac. VI.454 K.: " εἰ μὲν οὖν ὥσπερ ἐν γεωμετρίᾳ καὶ ἀριθμητικῇ συνεφωνεῖτο πάντα τοῖς γράψασι περὶ τροφῆς, οὐδὲν ἂν ἔδει νῦν ἡμᾶς ἔχειν πράγματα γράφοντας αὖθις ὑπὲρ τῶν αὐτῶν ἐπὶ τοσούτοις τε καὶ τοιούτοις ἀνδράσιν." If, as in geometry and arithmetic, everything was agreed upon by those who wrote about food, there would now be no need for us to engage in these works, writing about them again in addition [to what was said] by so many different men.

[2] On sarkotics (promoting the growth of flesh), see SMT XI.711.15–19; daknodes, see XI.621–627 K.

[3] pace van der Eijk translates ἐκ τῆς αὐτῆς εὕρομεν τὸ φάρμακον τοῦτο κράσεως as “we will discover the medicinal power from its mixture itself” (284n16). I take Galen’s point is that one can find the mixture (krasis) of the drug using qualified experience, just as one can find the mixture using taste or smell, which would suggest the ἐκ here refers to what the drug is composed out of (ἐκ), rather than the ground of the discovery.

[4] Must be τὰ κυδώνια μῆλα, mentioned by Galen at Alim. Fac. 6.602.1-603.10 K; also, San. Tu. VI.285 K., VI.450 K. and MM, e.g., X.906 K. as an eye cure. The same cure (?) mentioned Comp. Med. Sec. Loc. XII.948 K. Dioscorides, Galen’s target, gives this as a poultice for eye inflammation, De mat. med. 3.24.3: βοηθεῖ δὲ καὶ ὀφθαλμῶν φλεγμοναῖς σὺν ἑφθῷ <μήλῳ> κυδωνίῳ ἢ μετὰ ἄρτου καταπλασθέν, διαφορεῖ καὶ φύματα μετὰ ὠμῆς λύσεως λεῖον ἑψηθέν. Also mentioned by Athenaeus of Naucratis (e.g., 3.20.17: τὰ δὲ κυδώνια, ὧν ἔνια καὶ στρουθία λέγεται; 3.20.39); Plutarch (attributing a saying about it to Solon), Moralia 279 F 4.

[5] So, we should expect the following structure to each entry: (1) heating, cooling, moistening, drying; (2) capacities that follow from these; (3) particular, non-predictable qualities. Would be interesting to see if the entries reflect this.