More trouble with the Definitions...

In On Cohesive Causes, Galen mentions that Athenaeus took over some causal theory from Posidonius, particularly the notion of the synectic or cohesive cause, i.e., the cause responsible for something remaining what it is.

According to Galen, Athenaeus distinguished cohesive causes from two other kinds of causes: preceding (or prohegoumena) causes and antecedent (or prokatarctic) causes. A preceding cause is something internal that over time leads to disease. Examples Galen gives are venom and poison. An antecedent cause is something that gets some process going (On Cohesive Causes 2.3, CMG Suppl. Or. II ed. Lyons p.54). Something like what Aristotle calls an efficient cause.

In the pseudo-Galenic Medical Definitions, we find entries for six kinds of causes, including cohesive, preceding and antecedent causes, as well as an entry for cause in general. In Kühn’s text of the Definitions, Athenaeus’ name appears in definition 155 (XIX 392-3K), the definition of the procatarctic or antecedent cause. Here’s the whole bit from the Definitions on causes:

“154. A cause is that which produces something in the body and is itself incorporeal. Or a cause is, as the philosophers say, what is productive of something or through which something comes to be. Cause is three-fold: there is the antecedent [prokatarctic], preceding [prohegoumenon] and cohesive [synectic].

155. So, an antecedent [prokatarctic] [cause] is that which, having produced the effect, is separate, as the bite [is separate] from the dog, the sting from the scorpion, and the inflammation which produces a fever [is separate from] from the sun. Athenaeus of Attaleia speaks in this way. The agent is a cause, i.e., the antecedent [cause]. Otherwise. The antecedent causes are whatever [causes] begin before the result is entirely complete and of which there is nothing preceding.

156. A preceding [prohegoumenon] cause is that which is constructed or co-produced by the antecedent cause and precedes the containing cause. Others in this way. A preceding cause is that which, when it is present, the result is present; when it increases, the result increases; when it decreases, the result decreases; and when it is removed, the result is removed.

157. A cohesive [synectic] cause is that which, being present, preserves the presence of the disease, but when removed, removes [the disease], as the stone in the bladder; as the hydatid [i.e., a sac filled with fluid unconnected to tissues], as the pterugion [i.e., some kind of obstruction on the eye]; as the enkanthis [i.e., another obstruction of the eye]; [and] as other such things called containing causes, things which the very best physicians [thought] not only [should be placed] in an account of causes, but also [thought were distinct] from settled conditions.

158. A self-complete [autoteles] cause is what produces an end itself by itself.

159. A contributing cause [sunaition] is that which has adequate power with another to produce the result, but it is not being able to produce [the result] on its own power alone.

160. A coöperator [sunergon] is a cause which, when something produces a result but with difficulty, contributes to its more easy generation, not able to produce something on its own.”

[392K] ρνδʹ. Αἴτιόν ἐστιν ὃ ποιοῦν τι ἐν τῷ σώματι καὶ αὐτὸ ἀσώματόν ἐστι. ἢ αἴτιόν ἐστιν, ὡς οἱ φιλόσοφοι λέγουσι, τό τινος ποιητικὸν ἢ δι’ ὅ τι γίνεται. τριπλοῦν δὲ αἴτιον· ἔστι δὲ τὸ μὲν προκαταρκτικὸν, τὸ δὲ προηγούμενον, τὸ δὲ συνεκτικόν.

ρνεʹ. Προκαταρκτικὸν μὲν οὖν ἐστιν ὃ ποιῆσαν τὸ ἀποτέλεσμα κεχώρισται ὡς ὁ δακὼν κύων καὶ ὁ πλήξας σκόρπιος καὶ ἡ ἀπὸ τοῦ ἡλίου ἔγκαυσις ἡ τὸν πυρετὸν ἐργαζομένη. Ἀθήναιος δὲ ὁ Ἀτταλεὺς οὕτω φησίν. αἴτιόν ἐστι τὸ ποιοῦν. τοῦτο δέ ἐστι τὸ προκαταρκτικόν. ἄλλως. τὰ προκαταρκτικὰ αἴτιά ἐστιν ὅσα προκατάρχει τῆς ὅλης συντελείας τοῦ ἀποτελέσματος καὶ ὧν οὐδὲν προηγεῖται.

ρνστʹ. Προηγούμενον αἴτιόν ἐστι τὸ ὑπὸ τοῦ προκαταρκτικοῦ ἤτοι κατασκευαζόμενον ἢ συνεργούμενον καὶ προη-|[393K] γούμενον τοῦ συνεκτικοῦ. οἱ δὲ οὕτως. προηγούμενον αἴτιόν ἐστιν οὗ παρόντος πάρεστι τὸ ἀποτέλεσμα καὶ αὐξομένου αὔξεται καὶ μειουμένου μειοῦται καὶ αἱρουμένου αἱρεῖται.

ρνζʹ. Συνεκτικὸν αἴτιόν ἐστιν ὃ παρὸν μὲν παροῦσαν φυλάττει τὴν νόσον, ἀναιρούμενον δὲ ἀναιρεῖ, ὡς ὁ ἐν τῇ κύστει λίθος, ὡς ὑδάτις, ὡς πτερύγιον, ὡς ἐγκανθὶς, ὡς ἄλλα τοιαῦτα συνεκτικὰ καλούμενα αἴτια, ἅπερ οἱ γενναιότατοι τῶν ἰατρῶν οὐκ ἐν αἰτίων μόνον λόγῳ, ἀλλὰ καὶ ἐκ παθημάτων τιθέντων ταῦτα.

ρνηʹ. Αὐτοτελὲς αἴτιόν ἐστι τὸ αὐτὸ καθ’ αὑτὸ ποιοῦν τέλος.

ρνθʹ. Συναίτιόν ἐστιν ὃ σὺν ἑτέρῳ δύναμιν ἴσην ἔχον ποιοῦν τὸ ἀποτέλεσμα, αὐτὸ δὲ κατ’ ἰδίαν μόνον οὐ δυνάμενον ποιῆσαι.

ρξʹ. Συνεργόν ἐστιν αἴτιον ὃ ποιοῦν ἀποτέλεσμα, δυσχερῶς δὲ, συλλαμβάνον πρὸς τὸ ῥᾷον αὐτὸ γενέσθαι, κατ’ἰδίαν τι ποιεῖν οὐ δυνάμενον.

[Galen] Definitiones 154-160, XIX 392-3 K

The phrase attributed to Athenaeus looks like a statement about antecedent causes: they are productive or efficient causes. This claim fits nicely with what Galen says in On Cohesive Causes. He tells us Athenaeus contrasted antecedent causes, causes of change, with cohesive causes, causes of stability.

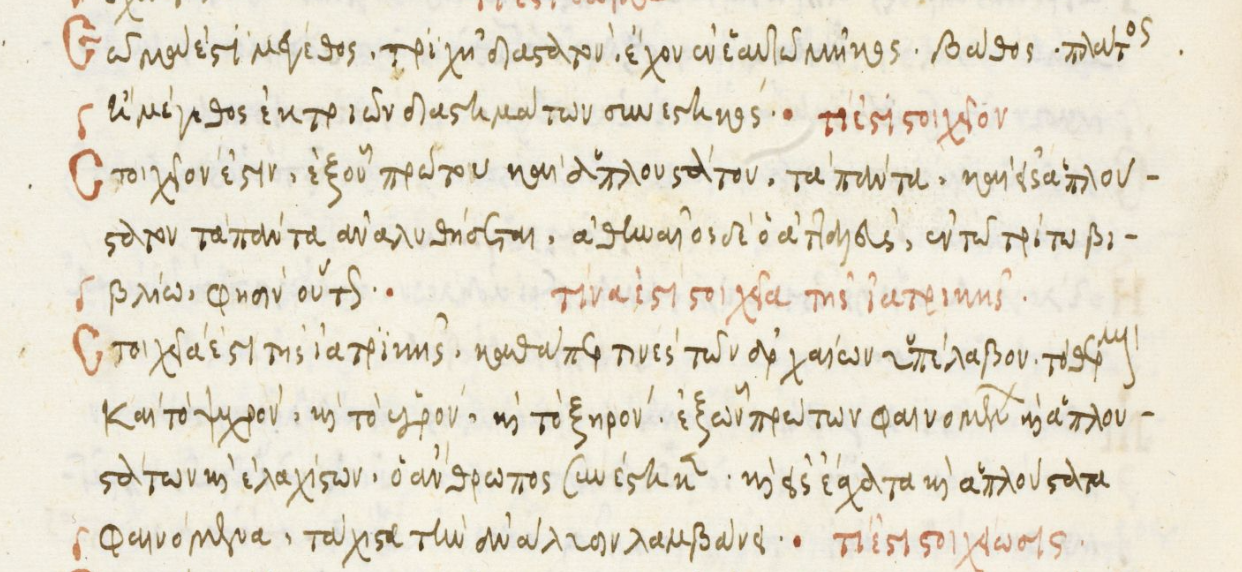

Oddly, we get a different picture from both the Aldine and and the BL ms. They put Athenaeus’ statement about efficient causes under the definition of the cohesive cause: