Galen on fear, depression and the health of the body: the story of Maiandros

Taken from a part of Galen’s commentary on Epidemics 6 that is extant in Arabic but not in Greek. I’m following Pfaff’s German translation of the Arabic. Galen is commenting on an aphorism which states that our mental and physical habits—things like daily routine, our home, our sex life and our mental habits—have an effect on our body’s health:

“The kinds of habits that influence our health: diet, shelter, work, sleep, sex, thought.”

ἔθος δὲ, ἐξ οἵων ὑγιαίνομεν, διαίτῃσι, σκέπῃσι, πόνοισιν, ὕπνοισιν, ἀφροδισίοισι, γνώμῃ.

Galen defends and elaborates on the claim using an example from his own experience, where being overcome by emotion led to illness and death.

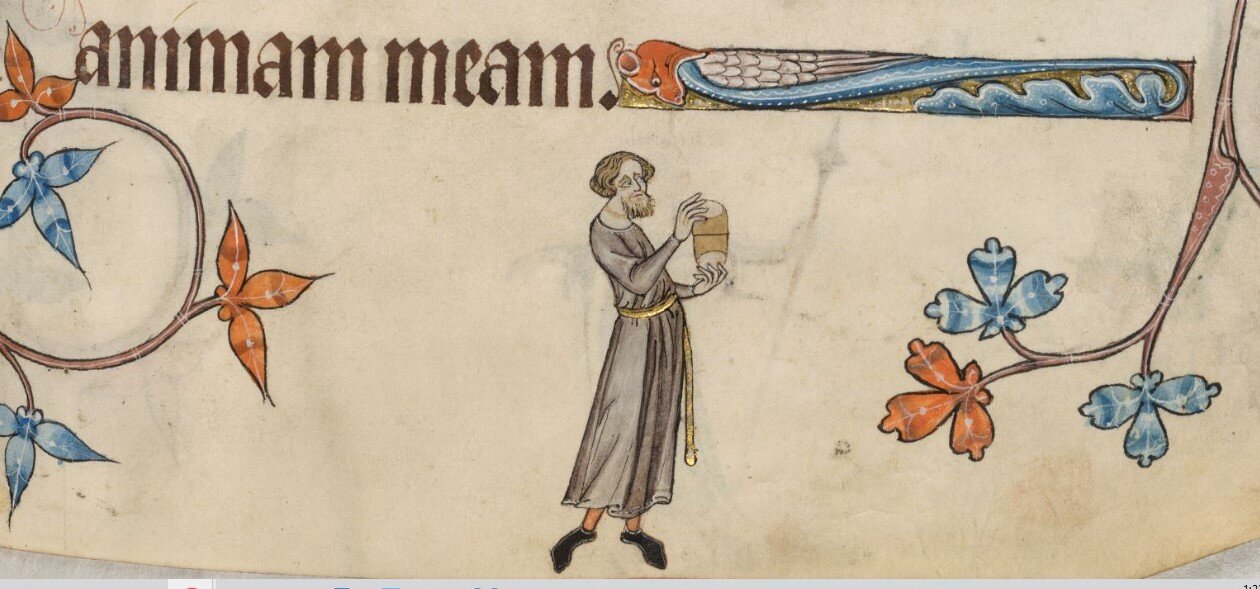

“I know a great number of people who were overcome by fear of death and whom this fear first made ill and then brought to death. Some were plunged into such fear by a dream; for others, such fear was caused by a premonition, or an omen, or a strange apparition they had, or the fall of a bolt of lightning. Some were brought to it by the sign they found in the entrails of the sacrificial animal, or by an augury of some kind of bird, as happened to the augur, Maiandros. This man was overcome by such a fear of death that he died of it, not to mention the illness he suffered. The story of Maiandros goes like this: he was a man from that part of Mysia which lies near the Hellespont and is a part of our province of Asia. His place of residence in this country was primarily Pergamon. The practice of augury was his occupation. It was his livelihood and his profession. Everyone who consulted him attested to his skill in his occupation. Now it was the custom of this Maiandros every year on his birthday to ask the gods to send him a sign by which he could see how he would fare in the following year. So one year he went out to observe the flight of birds and saw an eagle flying in a way that signified death. It then became certain in his soul that this was a sign from which there was no escape. He went back to the city from the place of the bird’s flight, slumped over, miserable and yellow in colour, so that those who met him asked him whether he was in any physical pain. To those he trusted, he told the truth. Then it came about that he lay sleepless for whole nights and was oppressed by sorrow all day long, so that he completely fell apart. Eventually mild, gentle fevers arose. When the fevers set in, his mind became so confused that he was outside himself and had to stay in bed. Two months after his birthday he died because his body gradually wasted away until it completely dissolved.”

So kenne ich eine große Zahl von Leuten, welche Furcht vor dem Tode überkam und welche diese Furcht zuerst krank machte und dann zu Tode brachte. Manche stürzte ein Traum in solche Furcht. Bei manchen erzeugte solche Furcht eine Ahnung oder ein Vorzeichen oder eine seltsame Erscheinung, die sie hatten, oder das Niedergehen eines Blitzstrahles. Manche brachte dazu das Anzeichen, welches sie in so den Eingeweiden des Opfertieres fanden, oder ein Augurium von irgendwelchen Vögeln, wie es dem Augur Maiandros erging. Diesen Mann überkam eine solche Angst vor dem Tode, daß er schon an ihr starb, ganz abgesehen von der Krankheit. Die Geschichte des Maiandros ist folgende: er war ein Mann aus dem Teile Mysiens, der dem Hellespont nahe liegt, und es ist ein Teil von unserem Lande Asien. Sein Aufenthalt in diesem Lande war meistens Pergamon. Die Ausführung des Auguriums war seine Tätigkeit. Sie war sein Broterwerb und sein Beruf. Jeder, der ihn zu Rate zog, bezeugte ihm seine Fertigkeit in seiner Tätigkeit. Nun war es die Gewohnheit dieses Maiandros, alljährlich an seinem Geburtstag Gott den Allmächtigen und Erhabenen zu bitten, ihm ein Zeichen zu schicken, an dem er erkennen könne, wie es ihm im folgenden Jahre ergehen werde. Und so ging er eines Jahres zur Beobachtung des Vogelfluges hinaus und sah einen Adler, der ih einer Form flog, die den Tod bedeutet. Da ward es ihm in seiner Seele gewiß, daß dies ein Zeichen sei, vor dem es kein Entrinnen gebe. Da ging er von dem Ort des Vogelfluges zusammengesunken, elend und gelb von Farbe nach der Stadt zurück, so daß diejenigen, welche ihm begegneten, ihn fragten, ob er irgend einen körperlichen Schmerz habe. Zu wem er Vertrauen hatte, sagte er die Wahrheit. Dann stellte es sich ein, daß er ganze Nächte schlaflos lag und ihn auch den ganzen Tag der Kummer bedrückte, so daß er ganz zerfiel. Schließlich traten leichte, sanfte Fieber auf. Als die Fieber sich einstellten, wurde sein Geist so verwirrt, daß er überhaupt nicht mehr bei sich war und das Bett hüten mußte. Zwei Monate nach seinem Geburtstage starb er dadurch, daß sein Körper allmählich dahin schwand, bis er sich ganz auflöste.

Galen, Commentary on Hippocrates‘ Epidemics 6.8, 485,25-486,12 Wenkebach/Pfaff