Galen on Sleep, Health and Heartbreak

More of Galen’s comments on the aphorism attributed to Hippocrates:

“The kinds of habits that influence our health: diet, shelter, work, sleep, sex, thought.”

ἔθος δὲ, ἐξ οἵων ὑγιαίνομεν, διαίτῃσι, σκέπῃσι, πόνοισιν, ὕπνοισιν, ἀφροδισίοισι, γνώμῃ.

Other cases: Maiandros, the augur who predicted his own death; a Cappadocian man who thought the sky would fall.

“In Rome, I recently saw a grammarian named Kallistos whose books were destroyed in the Great Fire that had burned the Temple of Peace. He grieved about this and could no longer sleep. First, he was taken with fever, and then, in just a short time, he wasted away until he died. I have seen quite a number of people like this—whose bodies waste away, be it from grief or from a bad mental state. I will limit myself to a few cases, because their number is too large. First, I mention the story of the mother of the lawyer Nasutus. The story of this woman is as follows. She received news that a woman she loved very much, who was seventy years old, was going by invitation to another place. She arrived there and returned home after having made the long journey. When she returned, she lay down on the bed and asked for some water to drink. The servant replied, “I'll bring it to you right away,” but she fell asleep before the servant returned with the water. By then, some time had passed without the people around the woman noticing anything. When, however, they called to her, she gave no answer. The servants were then compelled to shake her, but she did not wake up. They examined her and touched her body to see what had happened. Her whole body was cold and it was clear that she was dead. They covered her with the clothes in which she had died. When the mother of Nasutus found out about this, it went to her heart so much that she could no longer sleep the way she usually used to do, and eventually she could no longer sleep at all. Her body wasted away from insomnia. She began to have a fever and four days after the news of her friend’s death, she too passed away.”

In Rom sah ich vor kurzem einen Grammatiker, namens Kallistos, dem seine Bücher bei dem großen Brand in Rom, bei dem der Tempel, der “Tempel des Friedens” heißt, verbrannte, vernichtet wurden. Darüber grämte er sich und fand keinen Schlaf mehr. Zuerst begannen bei ihm Fieber, und dann in nicht langer Zeit siechte er dahin, bis er starb. Ich habe noch eine ganze Anzahl derartiger Menschen gesehen, deren Körper dahinsiechte, sei es aus Gram oder einer schlechten Geistesverfassung. Ich beschränke mich auf ein paar Fälle, da ihre Zahl ja zu groß ist. Zuerst erwähne ich die Geschichte der Mutter des Rechtsgelehrten Nasutus. Die Geschichte dieser Frau ist folgende: Sie erhielt die Nachricht, daß eine Frau, die sie sehr liebte und die siebzig Jahre alt war, nach einem anderen Orte auf eine Einladung hin ging. Sie war dort eingetroffen und auch wieder zurückgekehrt, nachdem sie den weiten Weg gemacht hatte. Nach ihrer Rückkehr hatte sie sich auf das Bett gelegt und verlangte etwas Wasser zu trinken. Der Diener hatte geantwortet: “Ich bringe es dir sofort.” Sie schlief aber ein, bevor der Diener mit dem Wasser zurück war. Es verging nun einige Zeit, ohne daß die Leute um die Frau etwas gemerkt hatten. Dann aber riefen sie sie an, aber sie gab keine Antwort. Die Diener sahen sich deshalb gezwungen, sie zu rütteln. Sie wachte aber nicht auf. Sie machten sich nun daran, die Sache zu untersuchen, und befühlten sie, um zu sehen, was mit ihr vorgegangen war. Ihr ganzer Körper war kalt, und es war klar, daß sie tot war. Sie deckten sie mit dem Kleid zu, in dem sie gestorben war. Als die Mutter des Nasutus dies erfuhr, ging es ihr so zu Herzen, daß sie sich nicht mehr zum Schlafen niederlegen konnte, wie sie es sonst gewöhnt war, und überhaupt keinen Schlaf mehr finden konnte. Da siechte auch ihr Körper infolge der Schlaflosigkeit dahin. Sie begann zu fiebern, und schon nach vier Tagen seit der Todesnachricht verschied auch sie.*

Galen, Commentary on Hippocrates‘ Epidemics 6.8, 486,19-487,12 Wenkebach/Pfaff

*Pfaff’s German translation of Hunayn’s school’s Arabic translation (the Greek is lost).

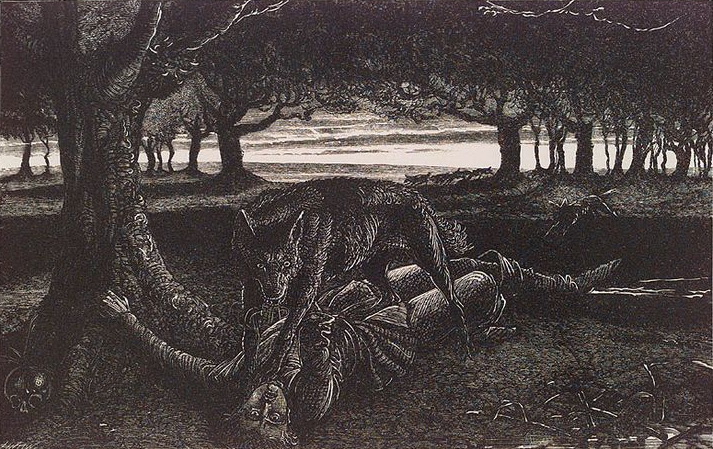

![“A dysputaciou[n] betwyx þ[e] saulee and þe body whe[n] it is past oute of þe body”. BL Add MS 37049 f. 81r. At the British Library.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56735f50a2bab8f9c97c115d/1552526197670-DLX87H3W1YJFFIVAO15U/bladdms37049.jpg)