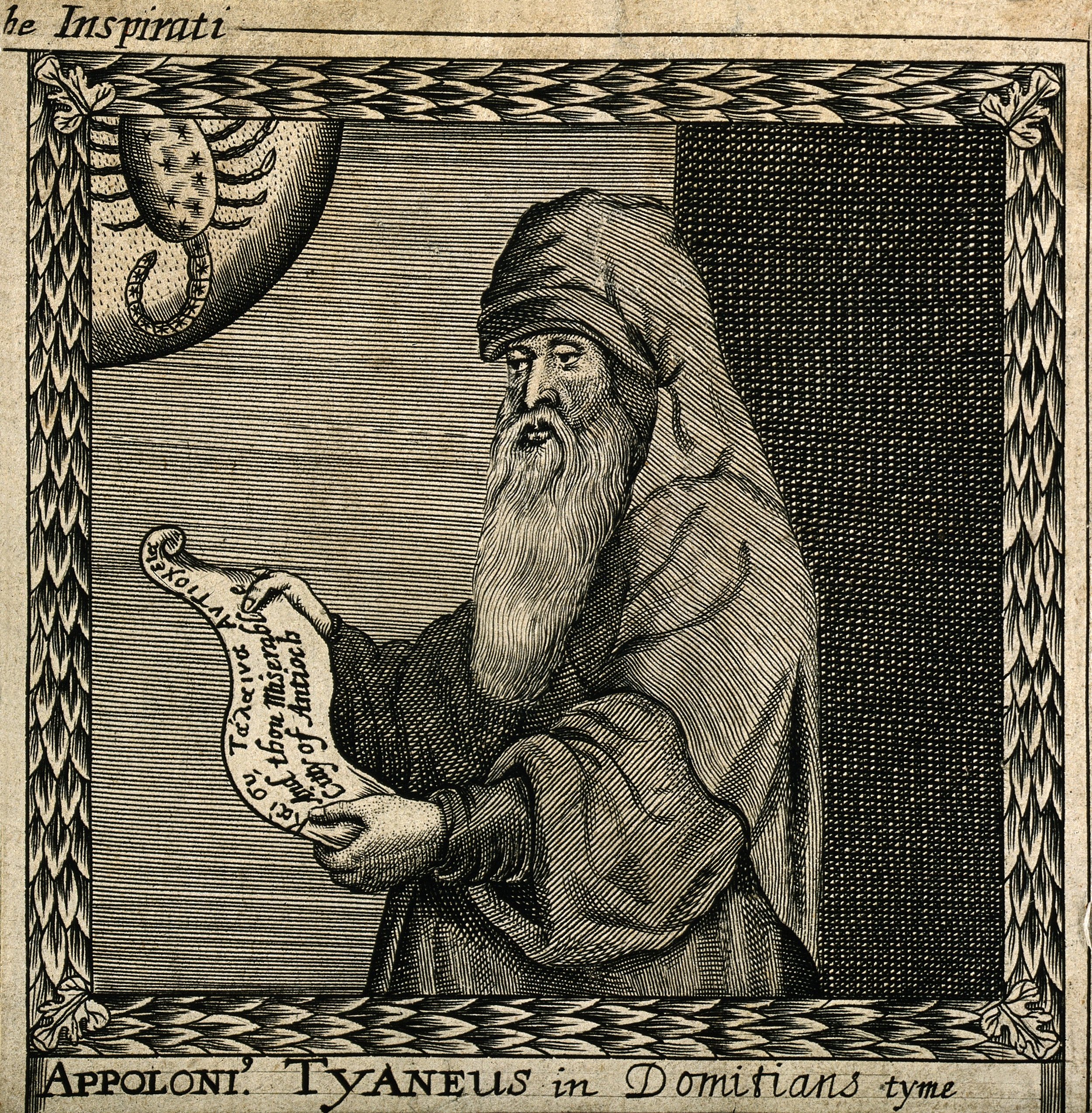

"Apollonius, from Tyana, philosopher, son of Apollonius and a citizen-mother of the nobility. When she was pregnant, his mother saw a daimon suddenly appear saying that he himself would be the one she gives birth to, he being Proteus the Egyptian. For this reason, he was assumed to be the son of Proteus. He was in his prime during the time of Claudius, Gaius and Nero, up until Nerva, at which time he died. He kept silence for five years, following Pythagoras. Next he set out for Egypt, then for Babylon to go to the Magi, then to the Arabs, and he collected from all of them countless numbers of their magical incantations. He composed such works as Rites of Initiation or On Sacrifices, Covenant, Oracles, Letters, Life of Pythagoras.

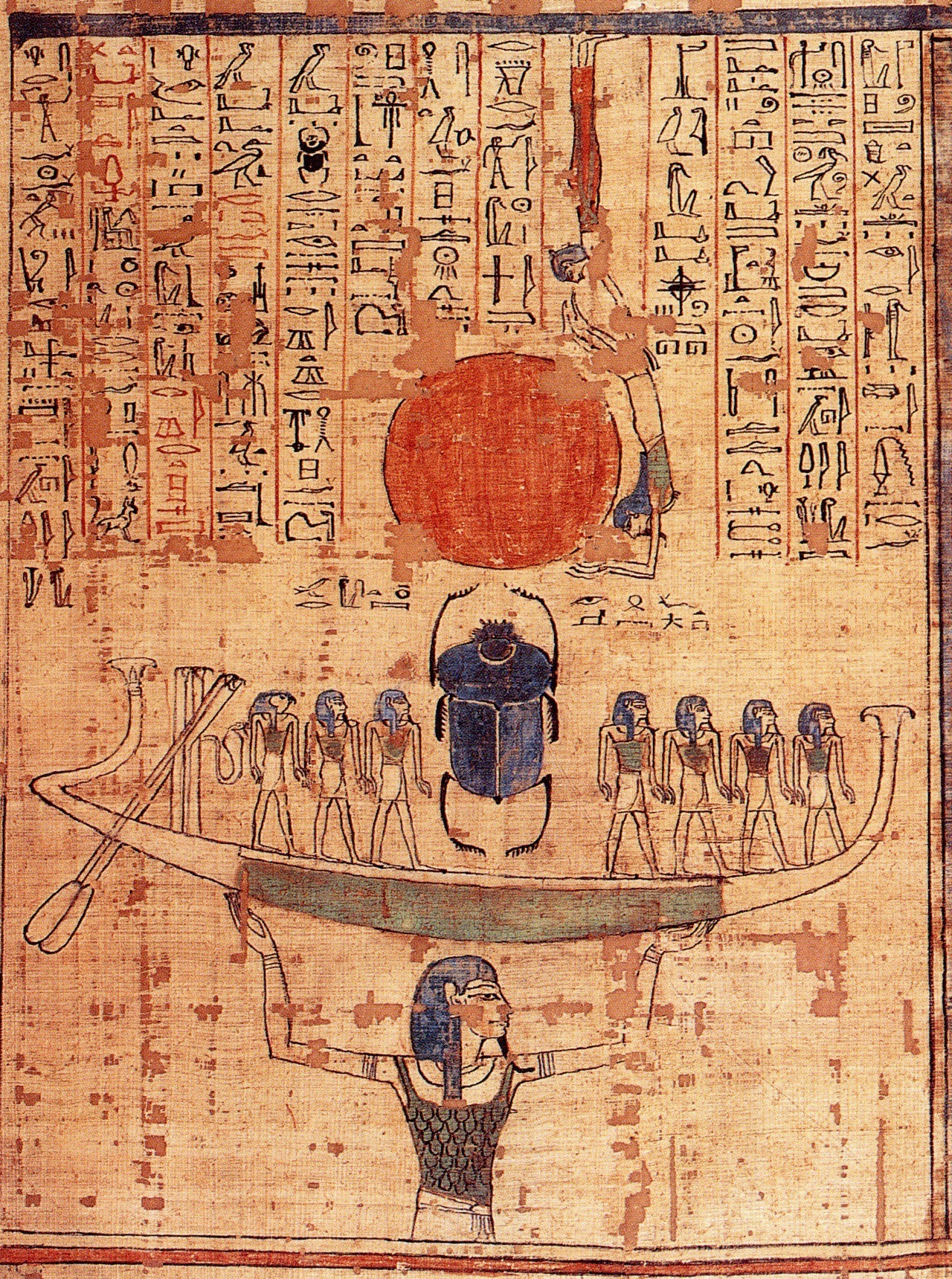

"Philostratus of Lemnos wrote a biography of him fitting for a philosopher. [He says] that Apollonius of Tyana exceeded Sophocles in continence, for the latter used to say "one escapes the raging and wild master, once one has come into old age", but Apollonius, through virtue and continence, did not give way to them even in his youth. About Apollonius, Philostratus says that he was more divine in his approach to wisdom than Pythagoras, since he overcame tyrants and he lived in a time not too ancient and not too modern. People do not yet recognize that he comes from the true philosophy, which he practiced philosophically and soundly. Rather, some people accept one thing about the man, others another. Still others consider him a Magus and attack him as unwise, because he learned from the Magi of Babylon, the Brahmin of India, and the Naked [ones] in Egypt. They poorly understand him. The fact is Empedocles, Pythagoras himself, and Democritus, associated with the Magi and said many demonic things, and yet they were never seduced by the art. And Plato, who went to Egypt and, like a painter when he adds colour to a sketch, infused his own writings with many things derived from the prophets and priests of that place was never thought to practice magic, and he most of all among people is envied for his wisdom.

"Regarding his ability to perceive and foretell many things, one should not attack Apollonius for the things he predicted in his wisdom, since then Socrates will also be attacked for the things he predicted, and Anaxagoras, who, at Olympia, when there was not the least sign it would rain, went into the stadium under a fleece, indicating a prediction of rain. It is wrong for them to attribute to Anaxagoras this foreknowledge that comes from wisdom and deny it to Apollonius. It seems to me, therefore, that one should not pay attention to the ignorance of the many, but describe the man with precision, both with respect to his chronology, when he said or did something, and with respect to the ways of his wisdom, by which he came to be thought daimonic and divine.

"I have collected reports from the cities that love him, from the temples which, having previously broken their rites, were restored by him, and from the things others wrote to him and he to others. He used to write to kings, sophists, philosophers, Elians, Delphians, Indians, and Egyptians about gods, about customs, and about laws, from whom [we can learn] what he did. The more accurate reports are from Damidos, his pupil.

"This Apollonius of Tyana had a good memory if anyone has. He kept his voice in silence, but gathered many things, and when he was one hundred years old had strength of memory beyond Simonides. He had a hymn to Memory which he would sign, in which he says all things wash away in time, but through memory time itself is ageless and immortal. Concerning Apollonius, look under the entry on 'Timasion' for other predictions.

"[It is reported] that this Apollonius said the following about Anaxagoras: he said he was from Clazomenae and the things he established were for cattle and camels, and that he would rather teach philosophy to cows than people. Crates from Thebes threw his property into the sea, making it useful for neither cows or men."

Ἀπολλώνιος, Τυανεὺς, φιλόσοφος, υἱὸς Ἀπολλωνίου καὶ μητρὸς πολίτιδος τῶν ἐπιφανῶν, ὃν κύουσα ἡ μήτηρ ἐπιστάντα δαίμονα ἐθεάσατο λέγοντα, ὡς αὐτὸς εἴη ὃν κύει, εἶναι δὲ Πρωτέα τὸν Αἰγύπτιον: ὅθεν ὑπειλῆφθαι αὐτὸν Πρωτέως εἶναι υἱόν. καὶ ἤκμαζε μὲν ἐπὶ Κλαυδίου καὶ Γαί̈ου καὶ Νέρωνος καὶ μέχρι Νέρβα, ἐφ' οὗ καὶ μετήλλαξεν. ἐσιώπησε δὲ κατὰ Πυθαγόραν ε' ἔτη. εἶτα ἀπῆρεν εἰς Αἴγυπτον, ἔπειτα εἰς Βαβυλῶνα πρὸς τοὺς μάγους, κἀκεῖθεν ἐπὶ τοὺς Ἄραβας, καὶ συνῆξεν ἐκ πάντων τὰ μυρία καὶ περὶ αὐτοῦ θρυλούμενα μαγγανεύματα. συνέταξε δὲ τοσαῦτα: Τελετὰς ἢ περὶ θυσιῶν, Διαθήκην, Χρησμοὺς, Ἐπιστολὰς, Πυθαγόρου βίον.

εἰς τοῦτον ἔγραψε Φιλόστρατος ὁ Λήμνιος τὸν φιλοσόφῳ πρέποντα βίον. ὅτι Ἀπολλώνιος ὁ Τυανεὺς ἐς σωφροσύνην ὑπερεβάλλετο τοῦ Σοφοκλέους. ὁ μὲν γὰρ λυττῶντα ἔφη καὶ ἄγριον δεσπότην ἀποφυγεῖν, ἐλθόντα ἐς γῆρας, ὁ δὲ Ἀπολλώνιος ὑπ' ἀρετῆς καὶ σωφροσύνης οὐδὲ ἐν μειρακίῳ ἡττήθη τούτων. ὅτι Φιλόστρατος λέγει περὶ Ἀπολλωνίου, θειότερον ἢ ὁ Πυθαγόρας τῇ σοφίᾳ προσελθεῖν τυραννίδων τε ὑπεράραντα καὶ γενόμενον κατὰ χρόνους οὔτ' ἀρχαίους οὔτ' αὖ νέους. ὃν οὔπω οἱ ἄνθρωποι γινώσκουσιν ἀπὸ τῆς ἀληθινῆς φιλοσοφίας, ἣν φιλοσόφως τε καὶ ὑγιῶς ἐπήσκησεν. ἀλλ' ὁ μὲν τὸ, ὁ δὲ τὸ ἐπαινεῖ τἀνδρός: οἱ δὲ, ἐπειδὴ μάγοις Βαβυλωνίων καὶ Ἰνδῶν Βραχμᾶσι καὶ τοῖς ἐν Αἰγύπτῳ Γυμνοῖς συνεγένετο, μάγον ἡγοῦνται αὐτὸν καὶ διαβάλλουσιν ὡς μὴ σοφὸν, κακῶς γινώσκοντες. Ἐμπεδοκλῆς τε γὰρ καὶ Πυθαγόρας αὐτὸς καὶ Δημόκριτος ὁμιλήσαντες μάγοις καὶ πολλὰ δαιμόνια εἰπόντες οὔπω ὑπήχθησαν τῇ τέχνῃ. Πλάτων δὲ βαδίσας ἐς Αἴγυπτον καὶ πολλὰ τῶν ἐκεῖ προφητῶν τε καὶ ἱερέων ἐγκαταμίξας τοῖς ἑαυτοῦ λόγοις καὶ καθάπερ ζωγράφος ἐσκιαγραφημένοις ἐπιβαλὼν χρώματα οὔπω μαγεύειν ἔδοξε, καίτοι πλεῖστα ἀνθρώπων φθονηθεὶς ἐπὶ σοφίᾳ.

οὐδὲ γὰρ τὸ αἰσθέσθαι πολλὰ καὶ προγνῶναι διαβάλλοι ἂν τὸν Ἀπολλώνιον, ἐφ' οἷς προὔλεγεν, ἐς τὴν σοφίαν ταύτην, ὡς διαβεβλήσεται καὶ Σωκράτης ἐφ' οἷς προὔλεγε, καὶ Ἀναξαγόρας, ὃς Ὀλυμπίασιν, ὁπότε ἥκιστα ὕοι, προελθὼν ὑπὸ κωδίῳ ἐς τὸ στάδιον ἐπὶ προρρήσει ὄμβρου. καὶ ἄλλα τινὰ ὑπὲρ Ἀναξαγόρου προτιθέντες ἀφαιροῦνται τὸν Ἀπολλώνιον τὸ κατὰ σοφίαν προγινώσκειν. δοκεῖ οὖν μοι μὴ περιϊδεῖν τὴν τῶν πολλῶν ἄνοιαν, ἀλλ' ἐξακριβῶσαι τὸν ἄνδρα τοῖς τε χρόνοις, καθ' οὓς εἶπέ τι ἢ ἔπραξε, τοῖς τε τῆς σοφίας τρόποις, ὑφ' ὧν ἔψαυσε τοῦ δαιμόνιός τε καὶ θεῖος νομισθῆναι.

ξυνείλεκται δέ μοι τὰ μὲν ἐκ πόλεων, ὁπόσαι αὐτοῦ ἤρων, τὰ δὲ ἐξ ἱερῶν, ὁπόσα ὑπ' αὐτοῦ ἐπανήχθη παραλελυμένα τοὺς θεσμοὺς ἤδη, τὰ δὲ ἐξ ὧν ἕτεροι πρὸς αὐτὸν ἢ αὐτὸς πρὸς ἄλλους ἔγραφεν. ἐπέστελλε δὲ βασιλεῦσι, σοφισταῖς, φιλοσόφοις, Ἠλείοις, Δελφοῖς, Ἰνδοῖς, Αἰγυπτίοις, ὑπὲρ θεῶν, ὑπὲρ ἠθῶν, ὑπὲρ νόμων, παρ' οἷς ὅ τι ἂν πράττοι: τὰ δὲ ἀκριβέστερα παρὰ Δάμιδος ἀκηκοώς.

οὗτος Ἀπολλώνιος ὁ Τυανεὺς διαμνημονικός τις ἦν εἴπερ τις ἄλλος, ὃς τὴν μὲν φωνὴν σιωπῇ κατεῖχε, πλεῖστα δὲ ἀνελέγετο, καὶ τὸ μνημονικὸν ἑκατοντούτης γενόμενος ἔρρωτο ὑπὲρ τὸν Σιμωνίδην. καὶ ὕμνος αὐτῷ τίς ἐστιν εἰς μνημοσύνην, ὃν ᾖδεν, ἐν ᾧ πάντα μὲν ὑπὸ τοῦ χρόνου μαραίνεσθαί φησιν, αὐτόν γε μὴν τὸν χρόνον ἀγήρω τε καὶ ἀθάνατον ὑπὸ τῆς μνημοσύνης εἶναι. ζήτει περὶ Ἀπολλωνίου καὶ ἕτερα προγνωστικὰ αὐτοῦ ἐν τῷ Τιμασίων.

ὅτι Ἀπολλώνιος οὗτος τάδε περὶ Ἀναξαγόρα ἔφη: καὶ γὰρ Κλαζομένιον ὄντα καὶ ἀγέλαις καὶ καμήλοις τὰ ἑαυτοῦ ἀναθέντα εἰπεῖν, προβάτοις μᾶλλον ἢ ἀνθρώποις φιλοσοφῆσαι. ὁ δὲ Θηβαῖος Κράτης κατεπόντωσε τὴν οὐσίαν, οὔτε προβάτοις ποιήσας ἐπιτήδειον, οὔτε ἀνθρώποις.

Suda, s.v. Apollonius of Tyana

*Philostratus' Life of Apollonius of Tyana, which documents his adventures touring the world talking with kings and gymnosophists is online at Livius.org.