“It is hard to believe that the man who set aside so widespread, tenacious and respectable a belief (sc. in the divine origin of prophetic dreams) accepted as fact the superstition that when a menstruous woman looks into the mirror its surface takes on a reddish tinge which may be difficult to remove.”

W.K.C. Guthrie, Review: Aristotle. Parva Naturalia. A revised text with introduction and commentary by Sir David Ross. (Oxford, Clarendon Press 1955. Pp. xi 355. Price £2.). Philosophy, 31 (118), 274-276.

“The story of the staining of the mirror by the eyes of a menstruating woman is thus a rationalization of a pre-existing superstition, the correctness of which Aristotle was not inclined to question, because he believed himself capable of explaining it.”

“Bei der Geschichte der Befleckung des Spiegels durch die Augen einer menstruierenden Frau haben wir es also mit einer Rationalisierung eines bereits vorhandenen Aberglaubens zu tun, dessen Richtigkeit Aristoteles nicht in Frage zu stellen geneigt war, weil er zu seiner Erklärung sehr wohl fähig zu sein glaubte.”

Philip van der Eijk, Aristoteles. De insomniis, De divinatione per somnum, Übersetzt und erläutert von Philip J. van der Eijk. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1994, p. 182.

Superstition

I’ve been collecting texts related to a passage On Dreams where Aristotle says menstruating women tarnish a mirror when they look at it.

I think this has to be the strangest passage in Aristotle. It is not the frighteningly casual misogyny. Aristotle could have questioned his sources, something he often does, like when he questions seers’ beliefs about prophesying by dreams or when he questions fishermen’s reports of parthenogenic fish in the second book of Generation of Animals. Instead, his credulity in this case just goes to show how deeply he believed in the corrupting influence of women. The way he says it, it’s like he’s saying the most obvious thing in the world: when menstruating women look at a very bright mirror, a cloudy, bloody spot forms on the surface. If it’s a new mirror, then getting the stain out is very difficult; if it’s an older mirror, it’s easier. Like most of the men we are about to encounter, questioning this does not come up.

But for now, let’s suppose he’s picking up a common superstition. For a superstition, it is extremely specific. It’s not a lot of detail, but still weirdly specific enough to wonder if he had polished some such mirrors himself.

First, he says the mirrors need to be very clean (i.e., bright), so probably a highly polished bronze. Second, he says the newer the mirror, the harder it is to remove the tarnish, which means it can be buffed out, it just takes some work.

In fact, one thing about Aristotle’s description that makes it different from other reports of this phenomenon (all of which were written by people after Aristotle, by the way) is this kind of detail. We’ll see Pliny’s description, which is closer to what I would expect from superstition—with all his fear-mongering about menstrual blood sterilizing trees, killing bees, and giving dogs rabies, not to mention dimming mirrors, rusting metal, and dulling the edges of swords, and all given with no attempt to explain any of this nonsense.

Philip van der Eijk, whose commentary is the only detailed look at the Aristotle passage, points to parallels similar to Pliny in Columella De re rustica XI 3, 50; Geoponica XII 20, 5 and 25, 2; and Solinus, Collectanea Rerum Mirabilium I 54-56 (PJvdE p. 184). And indeed, they simply seem to take over Pliny’s account.

Aristotle, however, focuses not just on the fact that women causes mirrors to dim, or even cause bloody spots to appear on them, but on variations of the phenomenon, both with respect to the object affected (new vs. old mirrors) and on the type of effect (easy vs. hard to remove).

There’s a part of me that wants to find some explanation for this, to start from the assumption that the phenomenon was real, even though menstrual blood had nothing to do with it.

Did women’s bronze mirrors in particular show spots of rust? Was there some ingredient common to cosmetics or bronze polish or something which got onto fingers and then onto the mirror—something like soda (sodium carbonate) or white lead (lead carbonate)?

I found a website that explains how to get all sorts of different patinas on bronze or copper using different chemicals, but nothing really stuck out. And there is absolutely no record of this phenomenon anywhere at all apart from these weird passages.

So: was what Aristotle described a common superstition among the Greeks and Romans? Not really. It’s mentioned about ten times, and even then, rarely with the detail Aristotle goes into.

Is it plausibly a real phenomenon? That bronze tarnishes, sure. But that a specific rust-red patina shows up on bronze mirrors, or on specifically the kind of bronze alloy used for mirrors in antiquity? Who knows, but I’d be very curious to find out.

Explanations

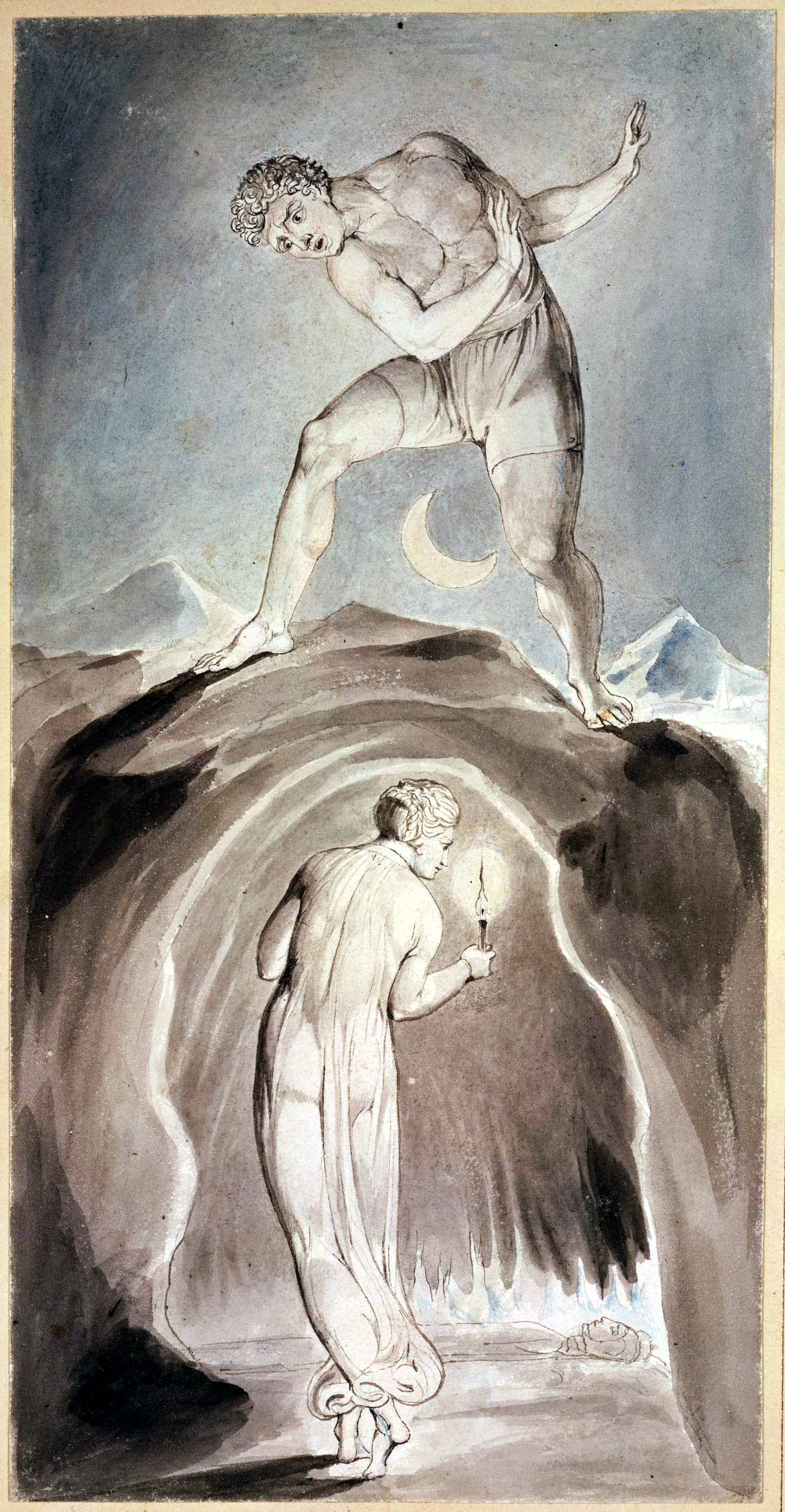

I won’t get too much into the details here. Aristotle thinks that the eyes of menstruating women act on the mirror, via the air, I guess by changing the colour of the air, which changes the colour on the surface of the mirror. How he could have felt this is a satisfactory explanation is a mystery to me. Proclus, when he reports it, associates it with the arts of magicians and sympathetic relationality. Granted, sympathy hadn’t been thought up in Aristotle’s time, but I think Proclus probably couldn’t stand Aristotle’s explanation, and so he threw a reference to it in his discussion of the cave allegory in order to help him out.

Incredibly, Michael of Ephesus doesn’t even mention it. His commentary on Aristotle’s explanation is almost as weird as Aristotle’s explanation itself. He writes as if Aristotle was talking about an echo: if a menstruating woman looks at herself in a mirror, the small detail of the red in her eyes’ will be reflected back to her (we need to keep in mind here that mirrors back then would not have had the clarity and brightness of mirrors today); but on any other surface, it would not be.

Marsilio Ficino uses another analogy. He likens it to condensation. As breath condenses on a cold piece of glass, so the visual ray, which is a spirituous substance obviously, condenses on the cold, smooth, dense mirror when it touches it leaving a spot of blood. Before and after this passage, Ficino assimilates this explanation to the explanation of the evil eye and other forms of optical contagion. In all these cases, the contagion doesn’t operate sympathetically, but more like poisoning: if the visual ray, which is vaporized blood, condenses inside the body of someone else, then the blood, which was originally harmful (as it would be if it came from a person who was ill or menstruating or whatever), causes a change for the worse.

Another thing: these explanations totally re-describe the phenomenon: Aristotle is thinking of something like tarnish or rust. Proclus, however, ends up describing something else, like looking through red glasses or something. Michael thinks the phenomenon is seeing blood spots in the eyes via the mirror. And Ficino thinks a spot of blood (not tarnish) appears on the mirror.

Now, Aristotle is not an extramissionist: he doesn’t think sight is analogous to touch, i.e., that visual rays go out of the eye and touch objects, bringing back information about them. At least he’s not usually an extramissionist—there is all the stuff in the Meteorology where he seems to be.

Aristotle also doesn’t think particles leave surfaces and then come to our eyes (the standard criticism of this view is that if they did, we could never see things as big as mountains, since they could not fit into our pupil).

Instead, he thinks objects act on the air which acts on our eyes. And here he is trying to explain that the reverse is true as well: our eyes act on the air, which acts on objects. And he thinks this happens all the time, but in mirrors it is especially noticeable since they are especially sensitive to these changes. So sensitive in fact that the image can (so to speak) burn into the mirror.

So Ficino’s explanation is not Aristotle’s, because Ficino is an extramissionist. Michael’s explanation is not Aristotle’s either (I think he’s embarrassed at the text too and trying to save it). Meanwhile, Proclus is doing his own thing, trying to make it into a kind of magical illusion.

Aristotle, however, although he doesn’t use the term, is treating the process as one akin to alchemy, where the nature of a metal is changed into something else. And by extension, whether the intends to or not, he is conceiving of women as alchemists by nature.

Texts

Aristotle, On Dreams

“A sign that the sense-organs sense even a small difference quickly is what happens in the case of mirrors, a subject which, even on its own, someone might pause to inquire into and puzzle about. At the same time, from the same facts it is clear that, just as sight is acted upon, so it also produces some effect. For in the case of very clean mirrors, when menstruating women observe their reflection, the surface of the mirror becomes like a bloody cloud. And if the mirror is new, it is not easy to wipe off a stain like this; if it is old, however, it is easier.

“The cause, as we said, is that sight is not only affected by the air, but it also produces a certain effect and change. For the eye is a bright object and has colour. Therefore, it is reasonable that during menstruation, the eyes are affected, just like any other bodily part, for they are naturally veiny. For this reason, when menstruation occurs because of a disturbance and bloody inflammation, while to us the difference in the eyes is not evident, it is nevertheless present (for the nature of semen and the menstrual fluid is the same). The air is changed by the eyes, and since the air near the mirror is continuous [with it], it produces an effect like the one it was affected with, and then it produces the effect on the surface of the mirror.

“As with cloaks, those that are especially clean are quickest to be stained. For a clean mirror accurately shows whatever it receives, and an especially clean one shows even the smallest changes. The bronze mirror, because of how smooth it is, is especially sensitive to any touch (one should think about the air’s touch like a kind of friction, like wiping-off or washing), and because it is clean, it becomes evident, no matter its size. But the cause of stains not leaving quickly from new mirrors is cleanliness and smoothness. For through them, the stain permeates both deeply and all over: deeply because of their cleanliness, all over because of their smoothness. In the case of old mirrors, however, the stain does not remain, because the stain cannot penetrate in the same way, but only superficially.

“From this it is evident that change is caused even by small differences, that sensation is quick, and that the sense-organ of colours is not only affected, but produces an effect in return. Evidence for what we’ve described are facts about wines and perfumery. For oil, when it has been prepared, quickly takes on the scents of things close by, and wines are affected in the same way. For they not only acquire the scents of things thrown into them or mixed in with them, but also the things placed near or growing near the vessels.”

ὅτι δὲ ταχὺ τὰ αἰσθητήρια καὶ μικρᾶς διαφορᾶς αἰσθάνεται, σημεῖον τὸ ἐπὶ τῶν ἐνόπτρων γινόμενον· περὶ οὗ καὶ αὐτοῦ ἐπιστήσας σκέψαιτό τις ἂν καὶ ἀπορήσειεν. ἅμα δ' ἐξ αὐτοῦ δῆλον ὅτι ὥσπερ καὶ ἡ ὄψις πάσχει, οὕτω καὶ ποιεῖ τι. ἐν γὰρ τοῖς ἐνόπτροις τοῖς σφόδρα καθαροῖς, ὅταν τῶν καταμηνίων ταῖς γυναιξὶ γινομένων ἐμβλέψωσιν εἰς τὸ κάτοπτρον, γίνεται τὸ ἐπιπολῆς τοῦ ἐνόπτρου οἷον νεφέλη αἱματώδης· κἂν μὲν καινὸν ᾖ τὸ κάτοπτρον, οὐ ῥᾴδιον ἐκμάξαι τὴν τοιαύτην κηλίδα, ἐὰν δὲ παλαιόν, ῥᾷον.

αἴτιον δέ, ὥσπερ εἴπομεν, ὅτι οὐ μόνον πάσχει ἡ ὄψις ὑπὸ τοῦ ἀέρος, ἀλλὰ καὶ ποιεῖ τι καὶ κινεῖ, ὥσπερ καὶ τὰ λαμπρά· καὶ γὰρ ἡ ὄψις τῶν λαμπρῶν καὶ ἐχόντων χρῶμα. τὰ μὲν οὖν ὄμματα εὐλόγως, ὅταν ᾖ τὰ καταμήνια, διακεῖται ὥσπερ καὶ ἕτερον μέρος ὁτιοῦν· καὶ γὰρ φύσει τυγχάνουσι φλεβώδεις ὄντες. διὸ γινομένων τῶν καταμηνίων διὰ ταραχὴν καὶ φλεγμασίαν αἱματικὴν ἡμῖν μὲν ἡ ἐν τοῖς ὄμμασι διαφορὰ ἄδηλος, ἔνεστι δέ (ἡ γὰρ αὐτὴ φύσις σπέρματος καὶ καταμηνίων), ὁ δ' ἀὴρ κινεῖται ὑπ' αὐτῶν, καὶ τὸν ἐπὶ τῶν κατόπτρων ἀέρα συνεχῆ ὄντα ποιόν τινα ποιεῖ καὶ τοιοῦτον οἷον αὐτὸς πάσχει· ὁ δὲ τοῦ κατόπτρου τὴν ἐπιφάνειαν.

ὥσπερ δὲ τῶν ἱματίων, τὰ μάλιστα καθαρὰ τάχιστα κηλιδοῦται· τὸ γὰρ καθαρὸν ἀκριβῶς δηλοῖ ὅ τι ἂν δέξηται, καὶ τὸ μάλιστα τὰς ἐλαχίστας κινήσεις. ὁ δὲ χαλκὸς διὰ μὲν τὸ λεῖος εἶναι ὁποιασοῦν ἁφῆς αἰσθάνεται μάλιστα (δεῖ δὲ νοῆσαι οἷον τρίψιν οὖσαν τὴν τοῦ ἀέρος ἁφὴν καὶ ὥσπερ ἔκμαξιν καὶ ἀνάπλυσιν), διὰ δὲ τὸ καθαρὸν ἔνδηλος γίνεται ὁπηλικηοῦν οὖσα. τοῦ δὲ μὴ ἀπιέναι ταχέως ἐκ τῶν καινῶν κατόπτρων αἴτιον τὸ καθαρὸν εἶναι καὶ λεῖον· διαδύεται γὰρ διὰ τῶν τοιούτων καὶ εἰς βάθος καὶ πάντῃ, διὰ μὲν τὸ καθαρὸν εἰς βάθος, διὰ δὲ τὸ λεῖον πάντῃ. ἐν δὲ τοῖς παλαιοῖς οὐκ ἐμμένει, ὅτι οὐχ ὁμοίως εἰσδύεται ἡ κηλὶς ἀλλ' ἐπιπολαιότερον.

ὅτι μὲν οὖν καὶ ὑπὸ τῶν μικρῶν διαφορῶν γίνεται κίνησις, καὶ ὅτι ταχεῖα ἡ αἴσθησις, καὶ ὅτι οὐ μόνον πάσχει, ἀλλὰ καὶ ἀντιποιεῖ τὸ τῶν χρωμάτων αἰσθητήριον, φανερὸν ἐκ τούτων. μαρτυρεῖ δὲ τοῖς εἰρημένοις καὶ τὰ περὶ τοὺς οἴνους καὶ τὴν μυρεψίαν συμβαίνοντα. τό τε γὰρ παρασκευασθὲν ἔλαιον ταχέως λαμβάνει τὰς τῶν πλησίον ὀσμάς, καὶ οἱ οἶνοι τὸ αὐτὸ τοῦτο πάσχουσιν· οὐ γὰρ μόνον τῶν ἐμβαλλομένων ἢ ὑποκιρναμένων ἀλλὰ καὶ τῶν πλησίον τοῖς ἀγγείοις τιθεμένων ἢ πεφυκότων ἀναλαμβάνουσι τὰς ὀσμάς.

Aristotle, On Dreams, Chapter 2, 459b23–460a32*

*In the 1935 Loeb, the Greek of this passage is translated into Latin instead of English ffs!

Pliny the Elder, Natural History

“But it is not easy that anything should be discovered that is more monstrous than woman’s menstrual fluid. New wine turns sour by coming near it, crops that are touched become barren, grafts whither, seeds of the garden dry up, fruit of trees by which she sits falls off, the brightness of mirrors are dimmed by reflecting her, the edge of iron is dulled, the brightness of ivory, bee hives die, bronze and even iron are seized by rust, and the air is seized by an awful smell. Dogs become rabid by tasting it and their bite is infected by an incurable poison. In fact, bitumen, too, which has an otherwise pliable and sticky nature and which floats at certain times of the year on the lake of Judaea, which is called Asphaltites, is not able to be divided up, as it sticks to everything it makes contact with, except a thread which is infected with this slime. Also ants, the tiniest animal, and sensitive to its presence, reject the tasty fruit which it was carrying never to return to it again.”

sed nihil facile reperiatur mulierum profluvio magis monstrificum. acescunt superventu musta, sterilescunt tactae fruges, moriuntur insita, exuruntur hortorum germina, fructus arborum, quibus insidere, decidunt, speculorum fulgor aspectu ipso hebetatur, acies ferri praestringitur, eboris nitor, alvi apium moriuntur, aes etiam ac ferrum robigo protinus corripit odorque dirus aera; in rabiem aguntur gustato eo canes atque insanabili veneno morsus inficitur. quin et bituminum sequax alioqui ac lenta natura in lacu Iudaeae, qui vocatur Asphaltites, certo tempore anni supernatans non quit sibi avelli, ad omnem contactum adhaerens praeterquam filo quem tale virus infecerit. etiam formicis, animali minimo, inesse sensum eius ferunt abicique gustatas fruges nec postea repeti.

Plinii Naturalis Historia 7.64–65

Proclus, Commentary on Plato’s Timaeus

“For even the shadows [i.e., on the wall the cave], which they say the images correspond to, have a nature of this kind. For these are likenesses of bodies and shapes, and they are in total sympathy with those things from which they arise, as it is also clear from the magic arts which profess to do things with images and shadows. And why mention only their powers? For even irrational animals have them, without any rational activity. For the hyena, they say, when it wants to eat, it casts its shadow on top of a resting dog and makes the dog a meal.* And Aristotle says that when a menstruating women looks into a mirror, the mirror and the reflected image are stained with blood.”

καὶ γὰρ αἱ σκιαί, αἷς τὰ εἴδωλα συζυγεῖν φησιν, τοιαύτην ἔχουσι φύσιν· καὶ γὰρ αὗται σωμάτων εἰσὶ καὶ σχημάτων εἰκόνες, καὶ παμπόλλην ἔχουσιν πρὸς τὰ ἀφ' ὧν ἐκπίπτουσιν συμπάθειαν, ὡς δηλοῖ καὶ ὅσα μάγων τέχναι πρός τε τὰ εἴδωλα δρᾶν ἐπαγγέλλονται καὶ τὰς σκιάς. καὶ τί λέγω τὰς ἐκείνων δυνάμεις; ἃ καὶ τοῖς ἀλόγοις ἤδη ζῴοις ὑπάρχει πρὸ λόγου παντὸς ἐνεργεῖν. ἡ γὰρ ὕαινα, φασί, τὴν τοῦ κυνὸς ἐν ὕψει καθημένου πατήσασα σκιὰν καταβάλλει καὶ θοίνην ποιεῖται τὸν κύνα· καὶ γυναικὸς καθαιρομένης, φησὶν Ἀριστοτέλης, εἰς ἔνοπτρον ἰδούσης αἱματοῦται τό τε ἔνοπτρον καὶ τὸ ἐμφαινόμενον εἴδωλον.

Proclus, In Platonis rem publicam commentaria 1.290

*I’ve talked about the magic of the hyena here.

Michael of Ephesus, Commentary on Aristotle’s On Dreams

“And so this is the general idea [of what Aristotle wrote], but in the passage, “for sight, too, is a bright object and one that has colour”, ‘sight’ means the whole eye. Also, he says that “it is reasonable” that the eyes change during the period of menstruation. For since the whole body changes at that time, necessarily the eyes also change. After talking about ‘the eyes’ in the neuter, he shifts and talks about them in the masculine, saying ‘for they [masculine] are naturally veiny’. For the eyes [masculine] are veiny. He also says that, as among menstruating women, a certain bloody affection is produced around the eyes, so too it happens to us during the emission of semen. This is not obvious when we look into a mirror because of the fact that semen is naturally white.

‘The bronze mirror, because of how smooth it is, is especially sensitive to any touch.’

“The phrase ‘is especially sensitive’ can be paraphrased as, ‘it makes stains on it that are especially sensible and obvious to us.’ For just as noises are produced especially on smooth bodies because of the fact that the air on them is not broken up or in general divided up into very fine parts, so too on smooth mirrors the blemish becomes obvious because of the fact that they are continuous and unitary, so to speak, because of the extreme smoothness of the mirror. But on those that are not smooth they are not observed, since they are divided up into very fine parts because of the unevenness of the reflecting surface, and what is very fine is not easily sensed. Therefore, the smoothness is the cause of continuity, while the cleanliness is productive of the clarity. For if it were clean but not smooth, then it will not produce sensation since it is broken up into small parts due to the unevenness. It is clear that, in the case of clean mirrors, stains become visible deep down. But that sensation that is quick also apprehends the images from the sensible object quickly, this is not clear.

‘Evidence for what we’ve described are facts about wines and perfumery.’

“Having said ‘that change is caused even by small differences,’ as proof of it he adds what happens in the case of perfumery: ‘For oil, when it has been prepared, quickly takes on the scents of things close by.’ For the scent of something close by, when it changes the oil, gives it a share of its own scent.”

Ἡ μὲν οὖν διάνοια αὕτη, ἐν δὲ τῇ λέξει τῇ «καὶ γὰρ ἡ ὄψις τῶν λαμπρῶν καὶ ἐχόντων χρῶμα» ὄψιν τὸν ὅλον ὀφθαλμὸν εἴρηκε. λέγει δὲ καὶ ὅτι εὐλόγως ἐν τῷ τῶν καταμηνίων καιρῷ τὰ ὄμματα μεταβάλλει· τοῦ γὰρ σώματος ὅλου τότε μεταβάλλοντος ἀνάγκη συμμεταβάλλειν καὶ τὰ ὄμματα. εἰπὼν δὲ τὰ «ὄμματα,» τρέψας εἶπε τὴν λέξιν ἀρρενικῶς εἰπών· «καὶ γὰρ φύσει τυγχάνουσι φλεβώδεις ὄντες·» οἱ γὰρ ὀφθαλμοὶ φλεβώδεις. λέγει δὲ καὶ ὅτι, ὥσπερ ἐπὶ τῶν γυναικῶν γινομένων τῶν καταμηνίων γίνεταί τι πάθος περὶ τὰ ὄμματα αἱματικόν, οὕτω γίνεται καὶ ἡμῖν ἐν τῇ τοῦ σπέρματος προέσει. οὐ φαίνεται δὲ ἐνορῶσιν εἰς τὸ κάτοπτρον διὰ τὸ τὸ σπέρμα φύσει λευκὸν εἶναι.

ὥσπερ δὲ τῶν ἱματίων, τὰ μάλιστα καθαρὰ τάχιστα κηλιδοῦται· τὸ γὰρ καθαρὸν ἀκριβῶς δηλοῖ ὅ τι ἂν δέξηται, καὶ τὸ μάλιστα τὰς ἐλαχίστας κινήσεις. ὁ δὲ χαλκὸς διὰ μὲν τὸ λεῖος εἶναι ὁποιασοῦν ἁφῆς αἰσθάνεται μάλιστα (δεῖ δὲ νοῆσαι οἷον τρίψιν οὖσαν τὴν τοῦ ἀέρος ἁφὴν καὶ ὥσπερ ἔκμαξιν καὶ ἀνάπλυσιν), διὰ δὲ τὸ καθαρὸν ἔνδηλος γίνεται ὁπηλικηοῦν οὖσα. τοῦ δὲ μὴ ἀπιέναι ταχέως ἐκ τῶν καινῶν κατόπτρων αἴτιον τὸ καθαρὸν εἶναι καὶ λεῖον· διαδύεται γὰρ διὰ τῶν τοιούτων καὶ εἰς βάθος καὶ πάντῃ, διὰ μὲν τὸ καθαρὸν εἰς βάθος, διὰ δὲ τὸ λεῖον πάντῃ. ἐν δὲ τοῖς παλαιοῖς οὐκ ἐμμένει, ὅτι οὐχ ὁμοίως εἰσδύεται ἡ κηλὶς ἀλλ' ἐπιπολαιότερον.

«Ὁ δὲ χαλκὸς διὰ τὸ λεῖος εἶναι ὁποιασοῦν ἁφῆς αἰσθάνεται μάλιστα.»

Τὸ «αἰσθάνεται μάλιστα» ἴσον ἐστὶ τῷ ‘αἰσθητὰς μάλιστα καὶ διαδήλους ἡμῖν ποιεῖ τὰς ἐν αὐτῷ κηλῖδας’. ὥσπερ γὰρ ἐν τοῖς λείοις σώμασι μάλιστα γίνεται ὁ ψόφος διὰ τὸ μὴ θραύεσθαι ἐν αὐτοῖς τὸν ἀέρα μηδ' ὅλως εἰς λεπτότατα κατακερματίζεσθαι, οὕτω καὶ ἐν τοῖς λείοις κατόπτροις αἱ κηλῖδες διάδηλοι γίνονται διὰ τὸ μένειν συνεχεῖς καὶ ὡς εἰπεῖν μία διὰ τὴν τοῦ κατόπτρου λειότητα. ἐν δὲ τοῖς μὴ λείοις οὐχ ὁρῶνται, ὅτι κατακερματίζονται εἰς λεπτότατα διὰ τὴν τοῦ ἐνόπτρου ἀνωμαλίαν· τὸ δὲ λεπτότατον οὐκ εὐαίσθητον. τὸ μὲν οὖν λεῖόν ἐστιν αἴτιον τῆς συνεχείας, τὸ δὲ καθαρὸν τοῦ διαδήλους γίνεσθαι. κἂν γὰρ ᾖ καθαρὸν μὴ λεῖον δέ, εἰς μικρὰ κατακερματισθὲν διὰ τὴν ἀνωμαλίαν οὐ ποιήσει αἴσθησιν. ὅτι δὲ ἐν τοῖς καθαροῖς ἐνόπτροις εἰς βάθος ἐμφαίνονται αἱ ἐν αὐτοῖς κηλῖδες, δῆλον. ὅτι δὲ καὶ ἡ αἴσθησις ταχεῖα καὶ ταχέως ἀντιλαμβάνεται τῶν ἀπὸ τῶν αἰσθητῶν εἰδώλων, οὐδὲ τοῦτο ἄδηλον.

«Μαρτυρεῖ δὲ τοῖς εἰρημένοις καὶ τὰ περὶ τοὺς οἴνους καὶ τὴν μυρεψίαν συμβαίνοντα.»

Εἰπὼν «ὅτι μὲν οὖν καὶ ὑπὸ τῶν μικρῶν διαφορῶν γίνεται κίνησις,» πίστιν τούτου παράγει τὰ περὶ τὴν μυρεψίαν γινόμενα. «τὸ γὰρ παρασκευασθὲν ἔλαιον ταχέως λαμβάνει τὰς τῶν πλησίον ὀσμάς·» ἡ γὰρ ὀσμὴ τοῦ πλησίον κινήσασα τὸ ἔλαιον μετέδωκεν αὐτῷ τῆς οἰκείας ὀσμῆς.

Michael of Ephesus In de insomniis commentaria, 66,4–67,9 Wendland

Marsilio Ficino, Commentary on Plato’s Symposium or On Love

“Aristotle writes that women, when they are menstruating, often make their mirror dirty with bloody specks when they look into it. I believe it happens for the following reason, because spirit [pneuma], which is the vapor of blood, appears to be blood so subtle that it escapes the eye’s observation, but when it condenses on the surface of the mirror, it becomes clearly visible. If it comes into contact with some less compact material, like a piece of cloth or wood, it cannot be seen because it does not remain on its surface, but penetrates into it. If it comes into contact with something dense but rough, like stones, bricks and the like, it is dissipated and broken up by the unevenness of its body. But on account of its hardness, the mirror keeps the spirit on the surface, on account of its evenness and smoothness, it prevents it from breaking up, and on account of its coolness, it condenses the extremely fine mist of the spirit into droplets. For the same reason, whenever we open our both and breath forcefully on glass, we sprinkle its surface with very fine saliva like dew. This is because the breath expelled from the saliva, when condensed on this material, returns to being saliva.”

Scribit Aristoteles, mulieres quando sanguis menstruus defluit, intuitu suo speculum sanguineis guttis sepe fedare. Quod ex eo fieri arbitror quia spiritus, qui vapor sanguinis est, sanguis quidam tenuissimus videtur esse, adeo ut aspectum effugiat oculorum, sed in speculi superficie factus crassior clare perspicitur. Hic si in rariorem materiam aliquam, ceu pannum aut lignum incidat, ideo non videtur quia in superficie rei illius non restat, sed penetrat. Si in densam quidem, sed asperam, sicuti saxa, lateres et similia, corporis illius inequalitate dissipatur et frangitur. Speculum autem propter duritiem sistit in superficie spiritum ; propter equalitatem lenitatemque servat infractum ; propter nitorem, spiritus ipsius radium iuvat et auget ; propter frigiditatem, rarissimam illius nebulam cogit in guttulas. Eadem ferme ratione quotiens hiantibus faucibus obnixe hanelamus in vitrum, eius faciem tenuissimo quodam salive rore conspergimus. Siquidem alitus a saliva evolans in ea materia compressus relabitur in salivam.

Marsilio Ficino, De amore: Commentarium in Convivium Platonis 7.4