‘mulier recte olet ubi nihil olet’

I’ve not had much time to post recently. I’ve been working on starting up Alchemies of Scent and trying to finish a few articles and books. But I’m also getting into some material on perfumery and other arts associated with Aphrodite / Venus. I had some time to translate and find a nice photo, so I thought I would put it up.

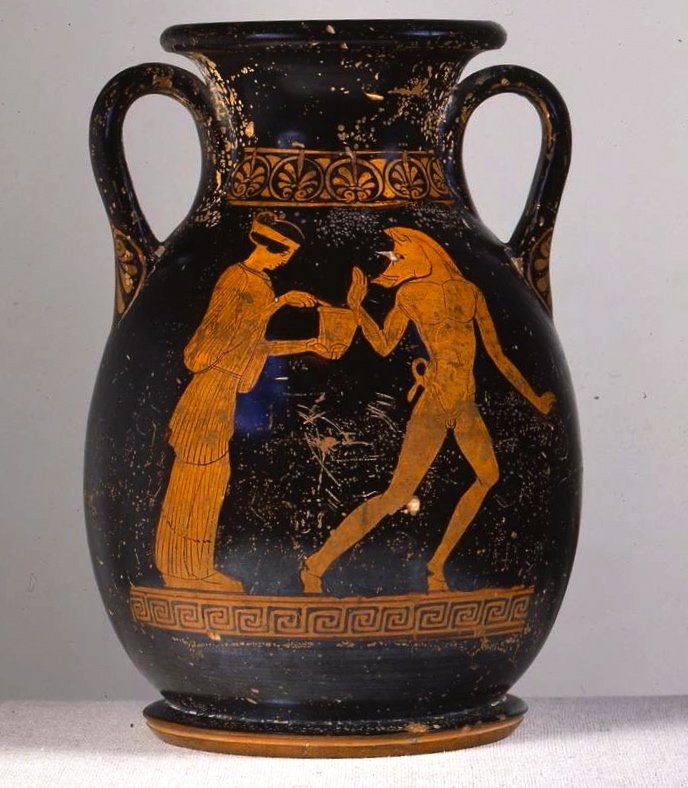

In the Greco-Roman lineage of texts I work with, there are many references to arts and technology of elegance, luxury and playfulness. They include perfumery, dyeing, fine metal working, embroidery, garment making, garland weaving, and also singing and other arts associated with the symposium.

I’ve started referring to them as the arts of Venus, “the Venerean arts,” since Aphrodite / Venus seems to govern them in astrological texts. As a nice bonus, Eros and Psyche figure in the arts’ frescoes at the house of the Vettii in Pompeii, hinting at a connection beyond astrology.

Being a luxury art doesn’t usually carry positive connotations for the authors I study. Instead, they are associated with things these authors consider to be morally inferior or wrong: wealth, femininity, impermanence, vanity and untrustworthiness.

The association between these authors’ moral categories and the Venerean arts is likely one reason why these arts were attacked and mocked by so many Greek and Roman voices that have survived and by many people who have followed them.

For example, we’re told Solon proclaimed a law that forbade Athenian citizens from being perfumers [1]. Xenophon’s Socrates says men have no need of perfume beyond the scent of sweat and olive oil, while women have no need for any scent at all beyond what is natural [2]. Plautus, in his Ghost Story (the Mostellaria, perhaps an adaptation of an earlier Athenian play), has a character say, mulier recte olet ubi nihil olet —‘a woman smells best when she smells of nothing at all’ [3]. Seneca reports a saying that one can tell a scoundrel by the fact that he wears perfume [4]. Doctors like Athenaeus or Galen say that a luxurious lifestyle also involves unhealthy behaviours, where ‘unhealthy behaviours’ often map closely on to behaviours these same figures take to be morally wrong (the causal direction here is not always clear).

Such condemnations of the Venerean arts are pretty familiar from surviving philosophical and political writings of the period.

Despite these critiques, however, the markets continued and the arts themselves survived. Even if the promoters of Solon and Socrates would want to make it appear so, the interest in and demand for luxury goods seems not to have exclusively provoked moral concern. There are many other interesting aspects of such arts, including their place in the history of science.

Still, I think it’s interesting that so many critics of these arts survive and how loud they have been in Greco-Roman literature’s history. I’m curious why we don’t find more impartial or even positive discussions of them, as, e.g., in Theophrastus or Dioscorides. I’m also curious what the original context of the discusisons about luxury might have been, since it is not obvious, and it is perhaps even doubtful, that such critical views were held by everyone.

For now, though, I’m looking into the artists of elegance and luxury themselves: how were they seen and grouped together at different times and how did they see themselves?

One set of sources I’ve come across are 2nd century CE astrological writings—texts where Aphrodite is given provenance over certain arts and offices. The following two are in Greek language by authors from the eastern and southern Mediterranean.

Sources for Veneran Arts in Astrological Writings

Here is Vettius Valens, who was originally from Antioch and perhaps later worked in Egypt:

“Aphrodite is desire and love. She is a sign of motherhood and nurturing. She produces offices of priests, schoolmasters, those with a right to wear a gold ring, and those with the right to wear a crown; she produces cheerfulness, friendship, companionship, the acquisition of property, the purchase of ornaments, contracts on favourable terms, marriages, arts of elegance, fine voices, song writing, sweet melodies, shapeliness, painting, mixing of pigments in embroidery, dyeing, and perfumery, and the inventors or even masters of these crafts, craftsmanship or trade to do with working of emeralds, precious stones, and ivory; and along her boundaries and portions of the zodiac, she makes gold-spinners, gold workers, barbers, people fond of elegance, and people who love playfulness.”

Ἡ δὲ Ἀφροδίτη ἐστὶ μὲν ἐπιθυμία καὶ ἔρως, σημαίνει δὲ μητέρα καὶ τροφόν· ποιεῖ δὲ ἱερωσύνας, γυμνασιαρχίας, χρυσοφορίας, στεμματοφορίας, εὐφροσύνας, φιλίας, ὁμιλίας, ἐπικτήσεις ὑπαρχόντων, ἀγορασμοὺς κόσμου, συναλλαγὰς ἐπὶ τὸ ἀγαθόν, γάμους, τέχνας καθαρίους, εὐφωνίας, μουσουργίας, ἡδυμελείας, εὐμορφίας, ζωγραφίας, χρωμάτων κράσεις καὶ ποικιλτικήν, πορφυροβαφίαν καὶ μυρεψικήν, τούς τε τούτων προπάτορας ἢ καὶ κυρίους, τέχνας ἢ ἐμπορίας ἐργασίας σμαράγδου τε καὶ λιθείας, ἐλεφαντουργίας· οὓς δὲ χρυσονήτας, χρυσοκοσμήτας, κουρεῖς, φιλοκαθαρίους καὶ φιλοπαιγνίους αὐτοὺς ἀποτελεῖ παρὰ τὰ τῶν ζῳδίων αὐτῆς ὅρια καὶ τὰς μοίρας.

Vettius Valens, Anthologia 1.1.6 (3,16–26) (English)

And here is Ptolemy, from Alexandria:

“When Aphrodite causes someone’s profession, she makes them persons whose activities lie in the scents of flowers or of perfumes, in wines, pigments, dyes, spices, or adornments, as, for example, sellers of perfumes, weavers of garlands, innkeepers, wine-merchants, sellers of drugs, weavers, dealers in spices, painters, dyers, sellers of clothing.”

ὁ δὲ τῆς Ἀφροδίτης τὸ πράσσειν παρέχων ποιεῖ τοὺς παρ’ ὀσμαῖς ἀνθέων ἢ μύρων ἢ οἴνοις ἢ χρώμασιν ἢ βαφαῖς ἢ ἀρώμασιν ἢ κοσμίοις τὰς πράξεις ἔχοντας, οἷον μυροπώλας, στεφανοπλόκους, ἐκδοχέας, οἰνεμπόρους, φαρμακοπώλας, ὑφάντας, ἀρωματοπώλας, ζωγράφους, βαφέας, ἱματιοπώλας.

Ptolemy, Tetrabiblos 4.4.4

[1] Athen. Deipn. 15.34, 519 Kaibel (Greek | English)

[2] Xen. Symp. 2.3 (Greek | English)

[3] Plaut. Mostell. 1.3 273 (Latin | English)

[4] Sen. Ep. 86.11 (Latin | English)