We went out picking Elderflowers to make cordial to last us through the summer, so I nerded out and dug into my medical sources to see what they had to say about them.

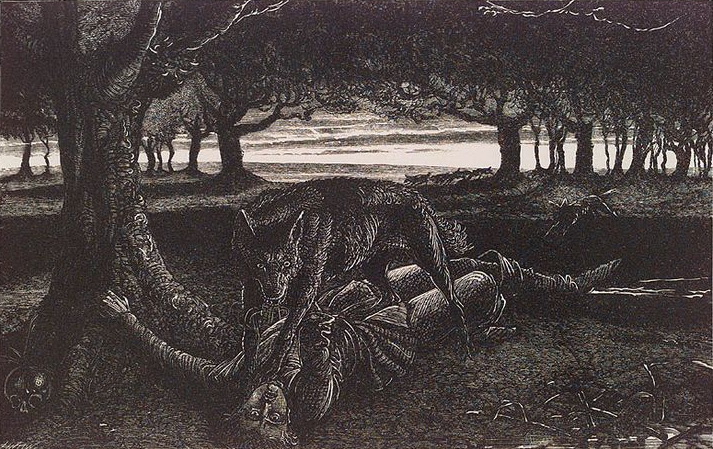

Now, there is a magical side to Elder that Greco-Roman medicine doesn’t talk much about. There is the Elder Mother who protects the tree from those who would harm it. There is the fact that the tree itself protects against witchcraft (or lightning, or caterpillars, depending on who you read). There are also stories that the cross of Jesus of Nazareth was made of Elder wood and that Judas Iscariot hung himself from an Elder tree. There is even a wonderful tradition in Oxfordshire to ‘bleed the elder’ at the King Stone on midsummer eve to commemorate the time when an Elder tree / witch turned an invading Danish King and his army to stone.

In English it is Elder, German Holunder, Ancient Greek ἄκτη, Latin sambucus (as in the drink, sambuca, which doesn’t have Elder in it anymore). For the botanical name, Linnaeus adopted the Latin, and the Latin has an interesting history itself. It derives from the Greek word σαμβύκη (sambuke), the word for some kind of harp made from some kind of wood, which might be Elder, but might not be. The wood of the Elder is hollow, so not the best wood for making string instruments. It is good for wind ones, though, which is why Pliny tells us the sabuci is used by shepherds to make horns or flutes. He also says that the shepherds believe the best wood comes from trees out of earshot of any roosters…

There is a book from 1631 published in Leipzig, written by Dr. Martin Blochwich, called Anatomia Sambuci, Anatomy of the Elder (translated into English by the Royal Society later in the 17th century), which goes over identification, recipes and its use in treatments. The Grimm brothers approach the subject from a different angle in their tale of Frau Holle.

Here are the medical sources on Elder (Sambucus nigra L.). As usual, don’t try these.

Dioscorides

1. Elder—double: for one is something tree-like that has reed-shaped branches, round, whitish and of good length; the leaves, either three or four spaced at intervals around the twig, similar to the walnut, but with a heavy scent and smaller; and at the ends of the branches, round umbels that have white flowers, and fruit resembling terebinth, purple-black, like a grape-bunch, juicy and wine-like.

2. The other one is called ground-elder, but by others marsh-elder. It is smaller and more like an herb, having a square stem with many joints; the leaves, at intervals around each joint, are pinnatifid, similar to almond, but notched around and longer, heavy-scented. The umbel at the end is like that of the one before, also flower and fruit. The root below is long, the width of a finger. The power and use of both are the same: cooling, able to drive out water, certainly bad for the stomach. Boiled like vegetables, the leaves purge phlegm and bile, and the soft stems, taken in a dish, produce the same effects.

3. Also, its root boiled with wine and given along with the routine diet benefits dropsical patients, and its helps those bitten by vipers likewise when drunk. Boiled with water in a sitz bath, it softens and opens up the womb and it straightens out the conditions associated with it. Also, drinking the fruit with wine produces the same effect, and it also dyes hair black when smeared on. New and soft leaves with (a poultice of) barley groats soothe inflammations and are suitable for burns and dog bites when used as a plaster. They also glue together fistulas and they help those with gout when used as a plaster with beef or goat fat.

1. ἀκτῆ · δισσή· ἡ μὲν γάρ τίς ἐστι δενδρώδης, κλάδους καλαμοειδεῖς ἔχουσα, στρογγύλους, ὑπολεύκους, εὐμήκεις· τὰ δὲ φύλλα τρία ἢ τέσσαρα ἐκ διαστημάτων περὶ τὴν ῥάβδον, καρύᾳ βασιλικῇ ὅμοια, βαρύοσμα δὲ καὶ μικρότερα, ἐπ' ἄκρων δὲ τῶν κλάδων σκιάδια περιφερῆ, ἔχοντα ἄνθη λευκά, καρπὸν δὲ ἐοικότα τερεβίνθῳ, ἐν τῷ μέλανι ὑποπόρφυρον, βοτρυώδη, πολύχυλον, οἰνώδη.

2. τὸ δ' ἕτερον αὐτῆς χαμαιάκτη καλεῖται, ὑφ' ὧν δὲ ἕλειος ἀκτῆ· ἐλάττων δὲ καὶ βοτανωδεστέρα, καυλὸν ἔχουσα τετράγωνον, πολυγόνατον· τὰ δὲ φύλλα ἐκ διαστημάτων περὶ ἕκαστον γόνυ τεταρσωμένα, ὅμοια ἀμυγδαλῇ, κεχαραγμένα δὲ κύκλῳ καὶ μακρότερα, βαρύοσμα· σκιάδιον δὲ ἐπ' ἄκρου ὅμοιον τῇ πρὸ αὐτῆς καὶ ἄνθος καὶ καρπός· ῥίζα δ' ὕπεστι μακρά, δακτύλου τὸ πάχος. δύναμις δὲ ἡ αὐτὴ ἀμφοτέρων καὶ χρῆσις, ψυκτική, ὑδραγωγός, κακοστόμαχος μέντοι. ἑψόμενα δὲ τὰ φύλλα ὡς λάχανα καθαίρει φλέγμα καὶ χολήν, καὶ οἱ καυλοὶ δὲ ἁπαλοὶ ἐν λοπάδι ληφθέντες τὰ αὐτὰ ποιοῦσι.

3. καὶ ἡ ῥίζα δὲ αὐτῆς ἑψηθεῖσα σὺν οἴνῳ καὶ διδομένη παρὰ τὴν δίαιταν ὑδρωπικοὺς ὠφελεῖ, βοηθεῖ δὲ καὶ ἐχιδνοδήκτοις ὁμοίως πινομένη· ἀφεψηθεῖσα δὲ μεθ' ὕδατος εἰς ἐγκάθισμα ὑστέραν μαλάσσει καὶ ἀναστομοῖ καὶ διορθοῦται τὰς περὶ αὐτὴν διαθέσεις. καὶ ὁ καρπὸς δὲ σὺν οἴνῳ ποθεὶς τὰ αὐτὰ ποιεῖ, μελαίνει δὲ καὶ τρίχας ἐγχριόμενος. τὰ δὲ φύλλα πρόσφατα καὶ ἁπαλὰ φλεγμονὰς πραΰνει σὺν ἀλφίτῳ καὶ κατακαύμασιν ἁρμόζει καὶ κυνοδήκτοις καταπλασσόμενα· κολλᾷ δὲ <καὶ> ὑποφοράς, καὶ ποδαγρικοῖς βοηθεῖ μετὰ στέατος ταυρείου ἢ τραγείου καταπλασσόμενα.

Dioscorides, On Medical Materials, 4.173

Galen

Elder, the large and tree-like, and the more herb-like one, which they also call ground-elder. Both have a drying and an adhesive and moderately dispersive power.

Ἄκτη ἥ τε μεγάλη καὶ δενδρώδης καὶ ἡ βοτανωδεστέρα, ἥν περ δὴ καὶ χαμαιάκτην ὀνομάζουσιν· ξηραντικῆς ἀμφότεραι δυνάμεώς εἰσι, κολλητικῆς τε καὶ μετρίως διαφορητικῆς.

Galen, On Mixtures and Powers of Simple Drugs, 6.21

Oribasius

Elder, the tree-like and the ground-elder, both have a drying and an adhesive and moderately dispersive power.

Ἀκτὴ ἥ τε δενδρώδης καὶ ἡ χαμαιάκτη ξηραντικῆς ἀμφότεραι δυνάμεώς εἰσι τῆς κολλητικῆς τε καὶ μετρίως διαφορητικῆς.

Oribasius, Medical Collections, 15.1.1.40

Aetius of Amida

Elder, the large and tree-like, and the one called ground-elder, both have a drying and an adhesive and moderately dispersive power. The decoction of the root when drunk helps dropsical patients.

Ἀκτή, ἥ τε μεγάλη καὶ δενδρώδης καὶ ἡ χαμαιάκτη καλουμένη, ξηραντικῆς ἀμφότεραι δυνάμεως εἰσί, κολλητικῆς τε καὶ μετρίως διαφορητικῆς· ὠφελεῖ δὲ καὶ ὑδρωπικοὺς τὸ ἀφέψημα τῆς ῥίζης πινόμενον.

Aetius of Amida, Medical Books, 1.19